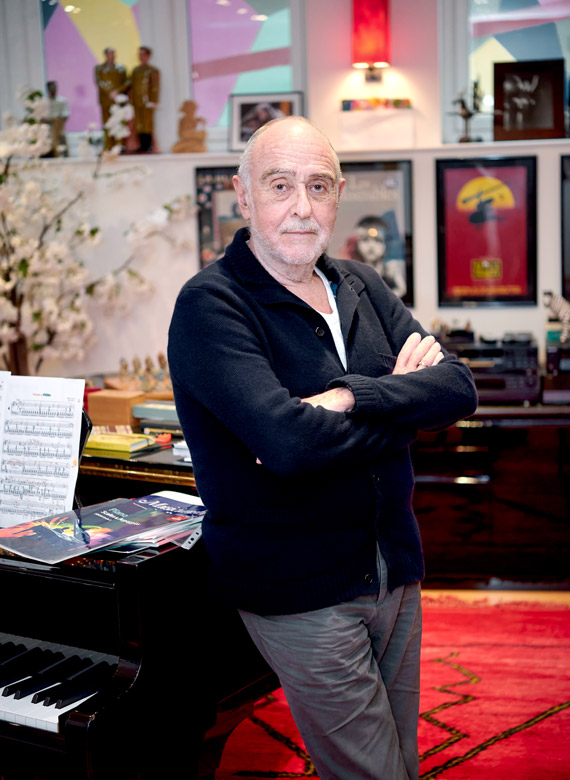

Claude-Michel Schönberg

Music as a raison d'être

![]() Reading Time: 11 minutes

Reading Time: 11 minutes

MUSIC AS A RAISON D’ÊTRE

When the world-renowned composer welcomes us to his Chelsea home, his frustration is palpable. We meet during a phase of respite between two lockdowns, but theatres remain closed and he admits to being as restless as a caged tiger. “If I’d have felt tired or if success had started to fade, now would be a good time to call it a day. But last year was one of the best years I’ve ever had!” At 76, Claude-Michel Schönberg still has new shows to bring to the stage, and productions to oversee on all continents. He is an accomplished and revered artist, so it is intriguing to find out exactly what it is that still keeps him going. He wrote a song which has sold over one million copies.

He composed Les Misérables – the longest-running musical in the West End (the second longest worldwide), which critics have often cited as one of the greatest musicals ever made. His shows have been produced on Broadway and on hundreds of stages over the world. He has received a Golden Globe, been nominated for an Oscar, and has won every possible accolade in the industry including the Laurence Olivier, Tony and Grammy awards. Millions of people have been moved to tears by his music, and one of his songs has become a protest anthem for oppressed people around the world.

But it is not money, fame, or the desire to leave his mark and change the world that drives Schönberg. In the course of this interview, we discover a man wholly consumed by the need to create music, who confesses that he had little merit in choosing his career, because music is the only way he knows how to live.

Could you tell us about your family background?

I come from a family of Hungarian Jews. A horse guard in Hungary stabbed my father and after that, he and my mother retained a lifelong rejection of authoritarian regimes. They fled persecution in the mid-‘30s and migrated to Vannes, in the west of France, where I grew up. Like millions of Jewish families who emigrated from Central Europe, my family story has a chaotic trajectory. I could have been born anywhere in the world.

During the war, I lost over half of my family members in Auschwitz and in the Budapest ghetto. During the Nazi occupation, Vannes’ anti-imperialistic identity revealed itself. The whole community took risks to protect my family; the priest even supplied some falsified christening certificates for us. My parents have always felt immensely grateful for being so warmly welcomed. No one ever made me feel like I didn’t belong.

From my childhood, I recall the joyful and generous spirit that characterised Jewish households. My father was an accountant back in Hungary, but had to do odd jobs until he trained as a piano tuner. Music was constantly being played at home. My mother loved having my friends over after school and she was always baking cakes for us. When she passed away, and many of my friends attended her funeral, they shared how fond they had been of my mother’s hospitality. It was only then that I realised how special my childhood had been.

Where does your musical aptitude come from?

According to my sister, I sang before I could even talk. My parents had a music shop, so I grew up surrounded by records and sheet music. By the age of seven, I knew three operas by heart. The piano was a sacred object in our house, and I have played since I was small. I had my first formal lesson when I was five. My teacher, Mademoiselle La Roche, explained that we would practice the scales and start with some pieces from Mozart and Chopin. To which I responded – allegedly with great confidence, that I would rather play my own compositions. In 1949 at the age of five, I vividly recall seeing Madame Butterfly, my first opera. During the curtain call, I was genuinely dismayed that the audience clapped for the singers when the person who wrote the music was not even given a mention. From a young age, I have been obsessed by the art of creating, not the performance.

Like many music lovers, I have a heightened sensitivity. Wagner moves me to tears. I have also experienced the “Stendhal syndrome”, a psychosomatic condition occurring when experiencing phenomena of great beauty. I remember attending a performance of Beethoven’s fifth concerto and when the pianist started playing, I began sweating profusely, nearly passing out. Beyond that, I realised fairly late in my life how uncommon my way of hearing music was. I have always been able to hear the wrong notes, and when I was coming up with a tune on my right hand, I could hear all the notes that should come from my left hand. I honestly have no merit; it is a gift I was born with. Music is not difficult for me.

Why did you decide to join Audencia?

There was never been a doubt in my mind that I wanted to work in music. The day my father died in 1958 – I was 14; I announced to my mother that I wanted to be an opera composer. She thought I was mad and my brother who was ten years older exclaimed: “That is not even a job”! Therefore, I made a deal with her: she would let me choose my path – even a risky career in music if I insisted, on one condition: firstly I had to finish my studies and get a degree. My mother could not support me financially so I had several part-time jobs, handwriting addresses on thousands of envelopes for my local council, and collecting returnable water bottles. My first meaningful job though was when I formed a rock band in 1963 – the early days of rock and roll, and we started touring.

After attending preparatory classes, I was offered a place at Sup de Co Paris, but I opted for Sup de Co Nantes so I could carry on playing with my band and earning some money. I cannot pretend that I joined Audencia by vocation; it was part of a plan that would grant me the freedom to dedicate my life to music.

What is your best memory at Audencia?

Shortly after I enrolled, I learnt that the student association was contractually entitled to use the “Théâtre Graslin” – the beautiful theatre downtown, once a year, for free. This information didn’t fall on deaf ears and I immediately volunteered to organise concerts. By pulling strings, I managed to persuade the iconic Barbara to come and perform in Nantes for the first time. I organised the event down to every last detail, from touring university campuses to promote it, to ordering the grand piano and planning an autograph session. The concert was sold out and Barbara was so pleased to have been so professionally taken care of that we saw each other several times after that. That was quite a highlight!

I was still performing with my band three nights a week, and one evening in my second year, the director of a music label came from Paris to listen to us. He told me that he would give me a job right after I graduated. Of those years, I remember spending much more time hanging around at the café than studying. I must have picked up one business notion or two though, because I still came out third in my year.

How did you start in the music business?

I graduated in June 1967 and the following September I started my first “proper job” at EMI in Paris. The director wanted to rejuvenate his team, so he hired myself and the singer and songwriter Michel Berger – to whom I remained close until his death in 1992. We had such fun writing songs and managing artists together. The context was very different then – we were pushing artistic projects out of pure passion, without any pressure or sense of competition.

In 1974, I wrote a song called “Le Premier Pas”. It was over 5 minutes long, with an unconventional structure, and everybody warned me that I would struggle to find an artist to sing it, let alone a radio station to play it. Alain Boulbil, a talented lyricist and my lifelong collaborator convinced me to sing it, despite my total lack of ambition to become a singer. The song ended up topping the French charts for weeks and sold over 1 million copies.

Writing the score for a musical takes a specific talent. When did you realise that your “calling” was to tell stories through music?

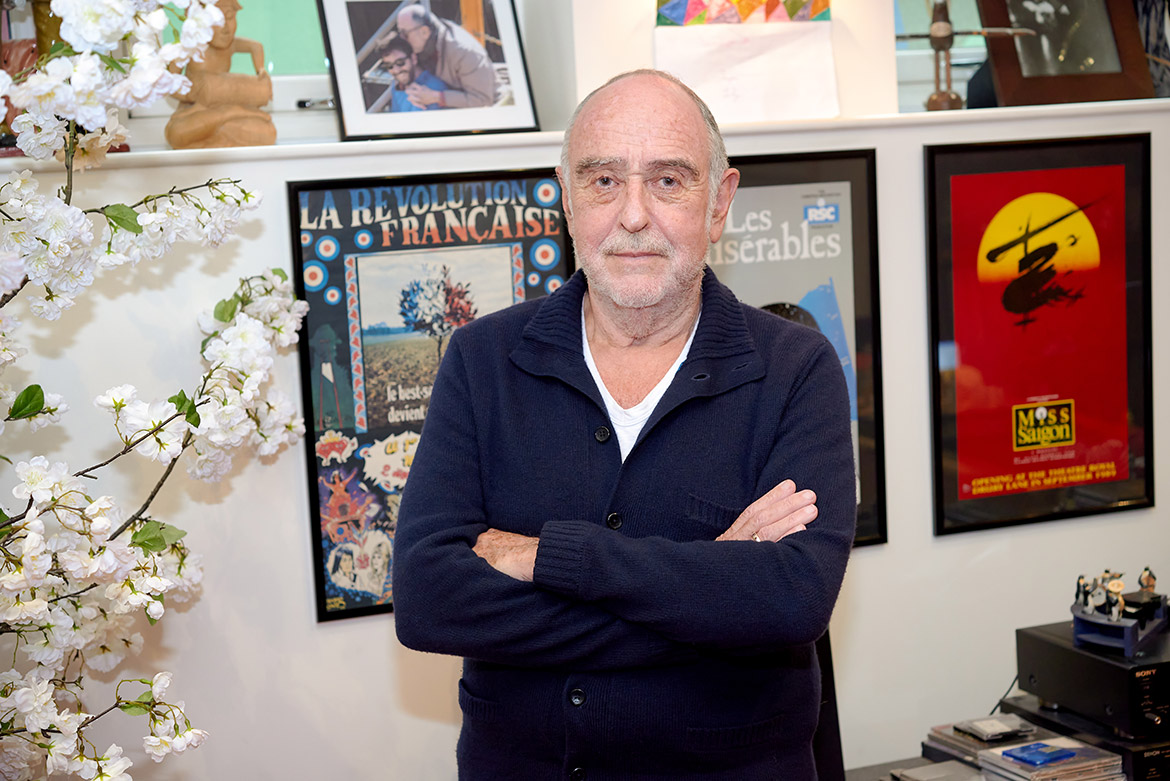

After my first hit I had many requests for songs but once I had written more than 250 in the traditional chorus-verse-chorus-verse-coda format, it became clear to me that I had other aspirations. After a discussion with Alain (Boulbil) who had just seen Jesus-Christ Superstar in New-York and had been blown away by it, we decided to work on a big show. We created “La Revolution Française”, a rock opera which was a success. From that moment on, we decided to stop composing songs and to focus entirely on musicals. In 1978, Alain attended a performance of “Oliver” in London and the little boy on stage reminded him of Gavroche. He realised that Les Misérables was the epic story we needed, and in five minutes, we made the most important decision of our lives. Later on, I had the idea to revisit Madame Butterfly and it became Miss Saigon, a modern version that took place in Vietnam. Then came other musicals and a few ballet scores.

What is your creative process?

I don’t work on commissions. Firstly, I have never waited for a producer to call me in order to start creating. And Alain and I both like to be in control of the whole process, whereas producers want to bring their own crew and have their own vision. Making a new show takes years. With Les Misérables for example, we started by reading Hugo’s book – all 1,200 pages – twice. Then for months we discussed the main themes and which scenes to focus on. We spent a year writing the script in French and when I later sat at my piano, I knew exactly what story I needed to translate into music. For this one as for most of our shows, Alain wrote the lyrics after I had finished composing. Knowing how to compose a song is at the core of the whole process and it can’t be improvised. Sadly, in many of today’s musicals, the show works, but taken out of their context, the songs are not that great.

Once a production has made it to various stages in the world, it still requires my attention, because of the live nature of this art. The audience must not realise that the actors have performed the show 200 times already, so I need to ensure that the stage buzzes with spontaneity, every evening.

What is the secret behind the success of a musical?

In the case of Les Misérables, it is mainly due to Victor Hugo’s genius. Our music serves the story well, but people universally are touched by the story. The reason why Susan Boyle created such a phenomenon when she sang “I Dreamed A Dream” from “Les Mis” was that she told her own story via the song. She was a bullied girl from Scotland who had always dreamt of becoming someone else. Catharsis happens when the audience hears a bit of their own story and gets to release powerful emotions.

What makes an artistic creation successful is a complicated alchemy that I don’t fully understand. Success is paradoxical in that it’s nothing short of a miracle, yet artists dedicate their lives to the pursuit of this miracle.

The night we opened Les Misérables in London, the critical reviews were appalling. The press refused to accept that a revered piece of classic literature could be converted into a popular show they compared with the Eurovision Song Contest. However, the following day, the show sold out for the following two months. The public had voted with their feet. We were also lucky that Princess Diana loved the show. She left in tears, promising that she would tell everyone she knew to come. We could not have dreamt of a better ambassador!

You are now a professor at Oxford and the Royal Academy of music. What are you trying to pass on?

I taught contemporary theatre at Oxford and I still give masterclasses at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Each year I work with 30 young artists who aspire to becoming singers or composers of musicals. I can tell within minutes which ones have remarkable musical technicality, sometimes greater than mine. I do insist on the technicality and what makes a good song. However, we also have discussions on a different level, with courses on the philosophy of composition. The challenge is to compose by turning inwards, whilst also being aware that the piece is going to be listened to and experienced by someone one day. But it’s not just about pleasing the public either. I am here to help bridge the gap between the composers’ intentions and the public’s perception.

What does music represent for you?

Simply said, nothing else in life interests me except art. Apart from music, I love theatre, literature, painting, sculpture. I have friends who have made millions through their hedge funds but I have zero interest or admiration for this type of career. Most of those friends envy me actually, and some even tell me that as children they had some artistic dreams that they could not pursue because their parents disagreed for example. I tell them what I tell my students: “Do not use your circumstances as an excuse for your lack of motivation. If you can spend an hour not thinking about music, there’s no point in hoping to succeed”. I hear music all the time: more than an obsession, it’s an abnormality. Music is my way of life.

Do you think music has some transformative powers at societal levels?

“Do you hear the people sing” is a song that has been adopted by protesters, in Taiwan, Hong-Kong, Turkey, the Philippines, Venezuela, or Chile. It seems to give people courage and hope. In Latin America it is actually called “Canción del Pueblo”. In October 2019, I wanted to fly to Caracas to support a young producer, but the travel agent didn’t want to sell me a ticket because the political instability made the country unsafe. I made it anyway, and I don’t regret it because when the cast started singing this song, 2,400 people stood up and sang at the top of their lungs. I will never forget this moving moment. It’s frightening to see how the world today is closer to the subject of Les Misérables and Miss Saigon than it was when we wrote them 30 years ago.

You are considered one of the most successful composers in the world. How do you define success?

What I hated most when I released the song called “Le Premier Pas” was when strangers constantly accosted me in the street as if we were best friends. I dislike promiscuity and familiarity, so I consider my situation today extremely fortunate, because I have the glory without the popularity. My shows are acclaimed around the world, I can go anywhere in peace, and people treat me with respect.

I don’t consider myself successful, it’s my work that is. I am mindful of making this distinction. And I am not in love with my work, just like there’s no painter in love with their painting. Once I have completed a piece, I quickly forget about the part that I have played, and move on. My interest shifts to the actors, singers, dancers, as I expect them to surprise me with their talent.

Why did you decide to settle in London?

The way that musicals are conceived in Paris is not my cup of tea. The producers want famous singers and famous songs, in the hope they will be played on the radio. My art is different, it’s theatre in music. London is where I found my professional family. It is also where my eldest son, an executive producer, lives, he works with theatrical producer Cameron Mackintosh, and we have often worked together. Besides, I love the courtesy of the British. In contrast, I find Paris awfully stressful.

What is your proudest achievement?

I have divorced and remarried, and my wife and ex-wife are best friends. They go shopping together to Victoria’s Secret… this is my most beautiful production!

More seriously, I don’t wake up every morning congratulating myself for having written successful musicals. I could cover my whole living room with gold discs but I choose only to display a few pieces of memorabilia, posters and some of my Tony and Grammy awards, as well as some childhood memories: my model planes, my chess sets.

The only thing I am proud of and astonished about is that I have accomplished all the dreams I had as a child growing up in Vannes. It is a rare privilege indeed. In addition, I feel that the last and only time I ever worked in my life was when I studied to graduate from Audencia in 1967! After that, it has been pure play and pleasure!