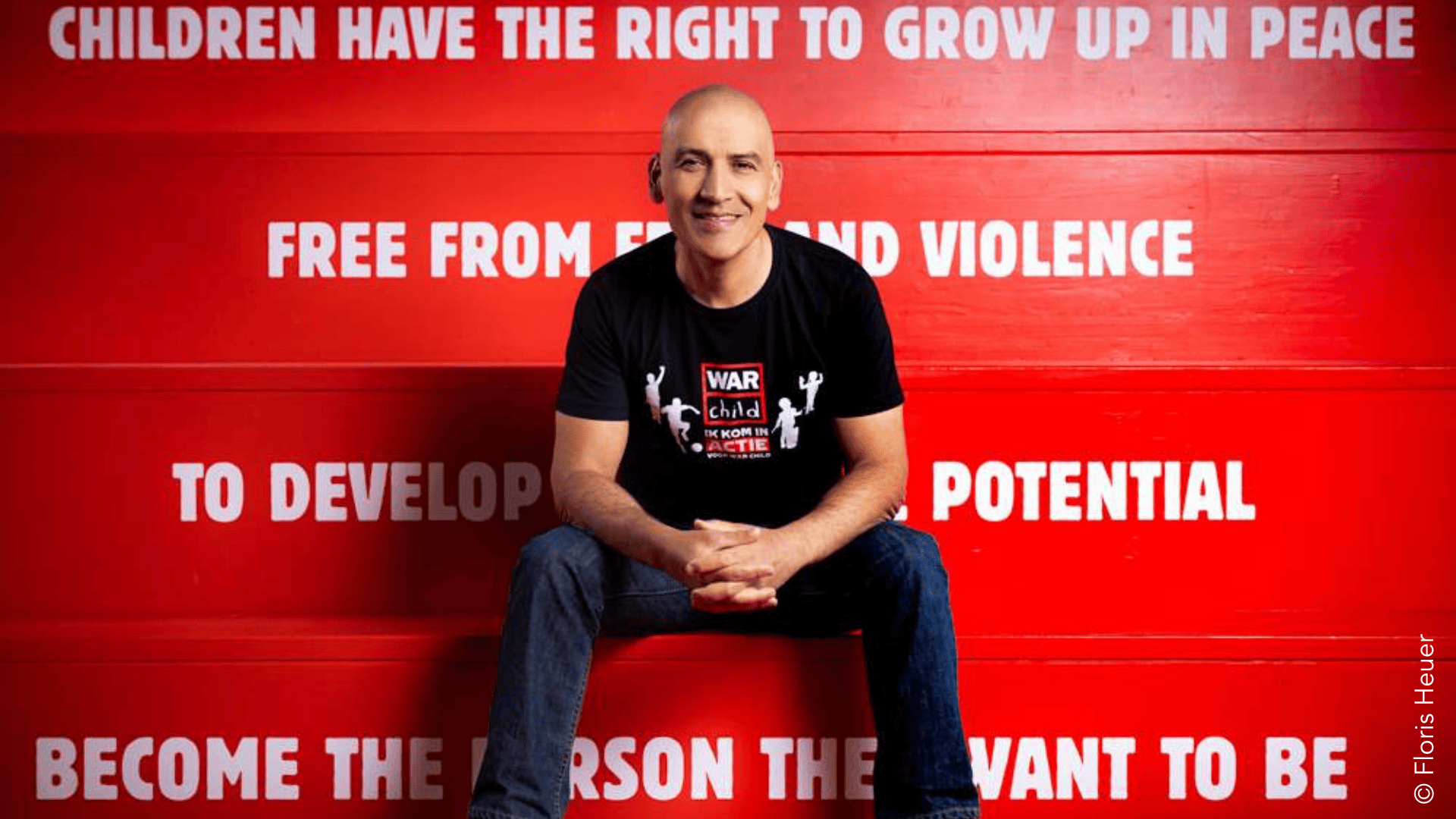

Ramin Shahzamani

Supporting vulnerable children reach for their potential

![]() Reading Time: 10 minutes

Reading Time: 10 minutes

CEO War Child

In 2021, Ramin Shahzamani was appointed CEO of War Child, an Amsterdam-based NGO that supports children affected by conflict around the world. Ramin, who has spent most of his career in the humanitarian sector, brings with him years of experience in international cooperation and fieldwork. He has been on the front line in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Colombia, Peru and Zambia.

In this brief presentation of Ramin Shahzamani, we mention no less than eleven countries. How else to describe the incredible international journey of a man whose career is driven by the desire to help the most disadvantaged?

Although he is realistic about the scale of the task - some 220 million children are affected by conflict around the world - Ramin is nonetheless fundamentally optimistic, an essential trait for working in the humanitarian sector.

You were born in 1970 in Iran; can you tell us about your childhood there?

The first eight years of my childhood in Iran were very normal and happy. I was a playful child sometimes getting into trouble but certainly enjoying life with my parents, brother and sister. My father was head of accounting and finance for Iran Oil, and my mother worked at home taking care of us.

From 1978, things started to change with the Iranian revolution. At first, it was quite fun because we didn’t always go to school and kids always like that! Then it became a bit more complicated because it was not a totally peaceful revolution. Our parents tried to protect us as much as possible and they did the best they could in a context where the changes soon had a radical impact on our lives.

How did you deal with leaving Iran at the age of 10?

Iran Oil’s offices were closed during the revolution. In 1979, the company asked my father to go to the UK to reopen the London office and we joined him there a year later. Then things got complicated for my family, and, without being too cryptic, my parents decided not to return to Iran but to head for Canada. I was eleven years old.

Arriving in London was tough as neither my brother nor I spoke English. We had to learn the language and adapt to a new culture in a difficult context: Iranian immigrants were stigmatised because of the Islamic revolution and the American hostage crisis. At the age of 11, you can already feel the discrimination. Children can be quite mean to each other and sometimes adults as well.

These events and major changes in a child’s life can shape their character, for better or for worse. Those years were important to me and certainly played a role in the decisions I made later on, giving me the desire to do something for the improvement of society.

What were the first years in Canada like and when did you consider that you had become Canadian?

For my parents at least, there was a lot of pressure. My father had a very good job at Iran Oil, and after he left, our lifestyle became more modest. Technically, we were not refugees, we had immigrant status, but in reality, the difficulties were much the same. However, my parents always placed an emphasis on education as the path to personal and professional success. As an immigrant, there was always a sense of having an additional obligation to succeed.

To be honest, the first three or four years in Canada were complicated, but things became easier once I mastered the language skills. I became more confident, developed friendships and started to feel like I belonged. Canada is a fascinating country for this. I always say I’m Iranian-Canadian and the beauty of it is that nobody questions it. I’m as Canadian there as anyone else and everyone considers me as such.

What kind of student were you, and what were your first jobs?

I think I was a pretty good student, but not outstanding. Like many teenagers, I struggled to find the link between subjects I enjoyed and what I wanted to do later. I really liked biology and microbiology, and later computer science, all of which were useful for my general knowledge but not directly for my choice of career.

After my first degree, I started an irrigation business with a friend I met at university. It was quite successful, but I realised that I needed other kinds of stimulation than the company was able to provide. My job lacked meaning and I struggled with this for several years before returning to university to get a degree in computer science. When I graduated, I could have gone to work in the private sector, but I had the opportunity to join a local NGO in India, as part of a Canadian government cooperation programme. That placement was my first experience of working outside Canada and it made me realise that social justice issues were at the top of my professional agenda.

So your time in India revealed your desire to be involved in the humanitarian sector

Absolutely. In fact, I have always been concerned with social justice and issues of peace and war in general. However, it was in India that I was first able to work in a structured way on social justice issues from a civil society perspective. After that, I applied for a job with the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy (WFM-IGP), a New York NGO. WFM-IGP is committed to the realisation of global peace and justice through the development of democratic institutions and the application of international law. I started out using technology for the communication purposes of the organization before getting involved in programmes, which clearly reinforced my calling to work in the humanitarian field.

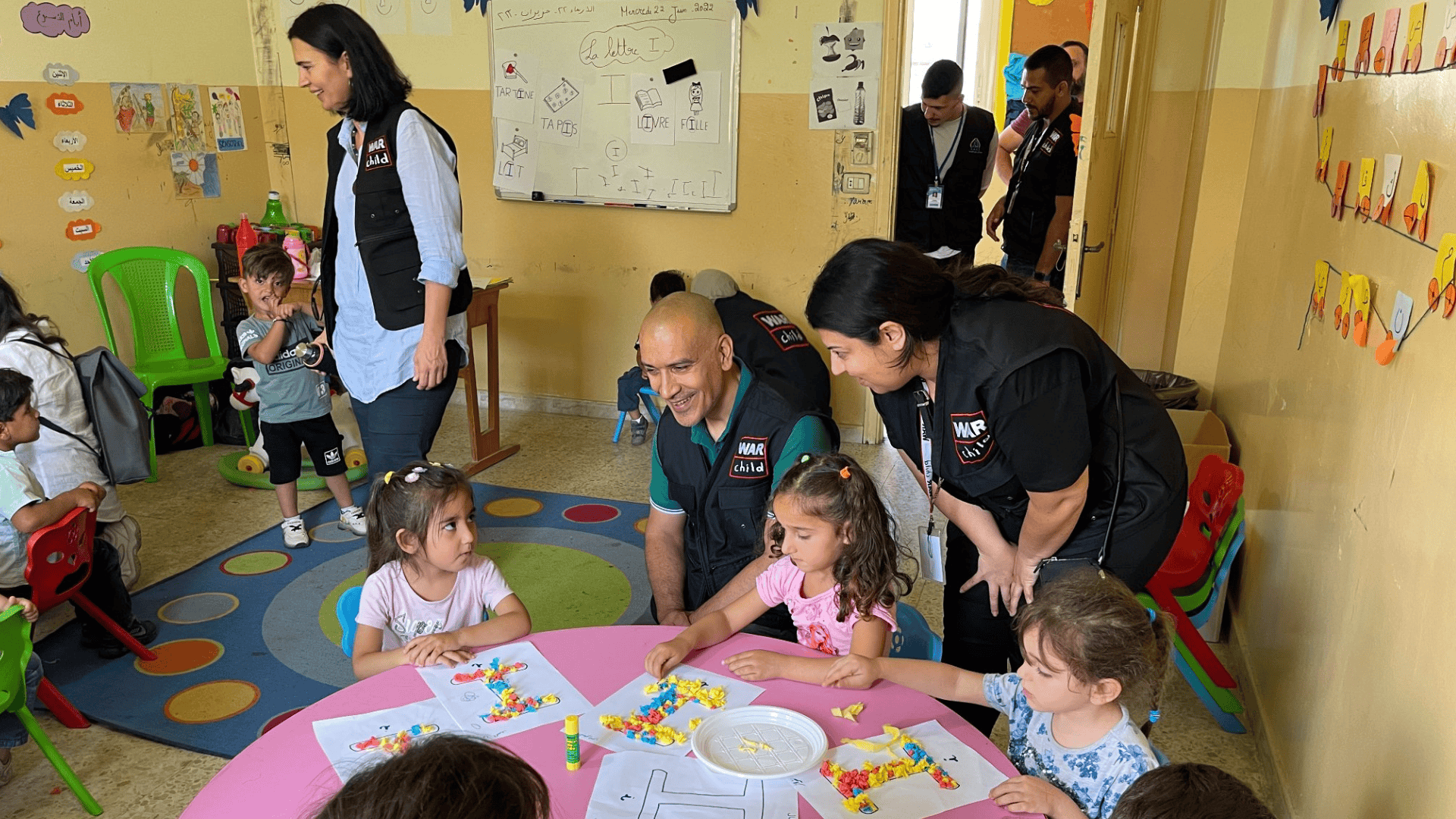

I moved to the D.R. Congo to be the Country Director of the NGO War Child and my work shifted from human rights to humanitarian and development work, but of course, they are closely related. War Child’s mission is to provide support to children affected by conflict. In the D.R. Congo, I remained in the field of human rights, children’s rights to be more exact with practical programmes. For me, it was a great opportunity to work on projects that were making a real difference to people’s lives.

You have managed local War Child branches around the world. To what extent did you see suffering and how did you deal with it?

Suffering was certainly omnipresent and I saw it directly because I was living there. However, going sometimes without electricity or not having access to clean water are comparatively small hardships. You do observe true suffering and feel close to it but are not experiencing it directly. We are in these countries as foreigners and we work for organisations that have certain safety standards and take care of their teams. However, it is not unusual to be confronted with difficult security situations. I have been in some. In some countries, you are somehow close to the fighting that breaks out. You hear it and sometimes you see it. When I was in Afghanistan, the country was volatile and unstable. Some of our friends were killed. There were a lot of precautions to take. So you try to have mechanisms to deal with the pressure and the stress. For some people it’s doing sports for example. In D.R. Congo we could go swimming in the lake which was probably as safe a place as anywhere. That was not the case in Afghanistan, but we could still take a week off every now and then to get together with colleagues outside the country, to rest before coming back to our work. This was not the case for our local colleagues.

You changed countries several times. Is international mobility inherent to the humanitarian sector?

I spent almost three years in the D.R.Congo, two in Afghanistan and four in Colombia with War Child, then five years in Peru and two in Zambia for the NGO, Plan International before becoming CEO of War Child at the organisation’s headquarters in Amsterdam. It is common practice in the humanitarian sector to change countries often, at least for people who have careers in the field and who need to be close to the support programmes.

Contracts generally last between two and five years depending on the organisation and the security conditions of the country. This allows individuals to gain both personal and professional experience. The rotations allow organisations to bring in new ways of thinking and approaches to the field.

When you are in the field, you usually hear about upcoming opportunities before your contract ends. You can then express your interest to the NGO’s management, who will decide whether you are the right candidate when a new position and destination become available. Career development is based on opportunities and the match with your skills.

What made you decide to enrol in the EuroMBA programme?

Even though non-governmental organisations are not based on profit, their set-up is very similar to any other business. You have to generate income and develop products and services. You build teams, have a strategy and all the departments that any other company has. At War Child, we have a marketing department, for example. I’ve always thought it important to bring a business mentality and approach to the places I have worked. Doing an MBA helped me gain useful business skills. Most of the courses on the EuroMBA programme were taught remotely but we also spent a residential week in each of the participating schools of the consortium, including Audencia. I was in Afghanistan then and it was very intense, but I was able to devote time to coursework because it wasn’t like I had much of a social life there! Due to time and life constraints, I was late in handing in my dissertation, but I graduated – finally – in 2022.

What does your position as CEO of War Child mean in practice? What are your priorities?

We have been working on two major transformational and strategic changes for War Child. The first is to our structure where our guiding principle is to transform into becoming a network expert organisation. We want to move from a European-based organisation to a global, decentralised organisation where power will be shared between the different locations where we operate. Decentralising expertise, so to speak. This means giving more decision-making power to the local offices where the impact of our work is strongest. This transformation reflects an underlying trend in the humanitarian sector, where issues of equity and equality are prominent.

The second is to scale up our work and reach more children that need our services. War Child has developed real expertise in certain areas such as education, mental health, psychosocial support and the protection of children affected by conflict. Currently, our programmes have an impact on around 300,000 children per year, but according to the latest UN statistics, around 220 million children worldwide are affected by conflict. There is a big disparity between our impact and actual needs. To undergo this transformation, we need to develop more scientific, rigorous methodologies, not only to implement them in our own programmes but also to make them available to other organisations.

My main job as CEO is to drive the levers that will make these strategic priorities a reality. I have a great team pushing in the same direction and moving forward. Of course, we have to be realistic about the huge challenges we face because of the suffering of so many people in the world, but that doesn’t stop us from being optimistic that we can make an impact with War Child. My team and I are convinced of this.

How has War Child been able to respond to the needs of children in Ukraine?

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, more than 7 million children have had their lives – including their education – irreversibly disrupted. Displaced from their schools, homes and, in many cases, their country, children are experiencing unthinkable compounded learning loss; first from the COVID-19 pandemic and now from war.

In May 2022, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MESU) and the largest education non-profit in Ukraine, Osvitoria, approached War Child Holland to find a solution to reach and teach mathematics and reading to some of their youngest learners – children in grades 1-4.

War Child Holland took on this challenge and began the process of rapidly adapting its already proven Education-in-Emergencies programme, Can’t Wait to Learn, to meet these new demands for greater scale. This required a re-programming of the app to make it available – for the first time – on personal IOS and Android devices, along with its standard practice of co-creation and curriculum alignment with the government. Each version of the app is also uniquely designed with local children, educators and artists to reflect the culture, language and look of the country to make the learning experience for children feel familiar as well as fun.

In addition we are working with local partners to provide mental health and psychosocial support in protected spaces for children. These methodologies have also been scientifically proven to reach positive outcome for children.

What are you most proud of at War Child?

I’m really proud of the direction we’ve taken at War Child and the fact that we’ve put two big transformational changes on track. Of course, we’re still a long way off, and I’ll be even prouder when we’ve achieved those two goals. After all, we could have just carried on working the way we already do, but instead, we’re taking a pretty bold path to challenge ourselves and make these transformations: sharing our power and looking at what it really takes to expand our impact and reach millions of children.

Do you have children of your own?

I have a stepdaughter who is 22 now. She was with us in Colombia and Peru before heading to France to become a pastry chef.

What and where would you like to be in ten years?

I must admit that I don’t look that far ahead. Professionally, my goal is to complete my task as CEO of War Child.

What are you going to do with your weekend?

This weekend is my partner’s birthday. One of the things we’re planning is to go and see an art exhibition that’s on in Amsterdam at the moment.

I read that music is important in your life. Can you tell us what it does for you?

Music does play a big role in my life. Of course, I have my preferences, but I like all kinds of music. Each one touches me in some way. It can be a rhythm I like or certain lyrics I can relate to. Music is also very important for War Child, which is supported by many musicians and has been built using creative methodologies to support children’s mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Therefore, I have a personal connection and a kind of organisational connection to music. I listen to everything. This morning, for example, I listened to Lennon Stella.