![]() Reading Time: 11 minutes

Reading Time: 11 minutes

CEO & Founder of Handiroad, serial entrepreneur

Stéphanie’s path to date has been one of ups and downs. She was diagnosed with a rare neurodegenerative disease and Asperger’s syndrome and her family struggled to accept her differences. At her lowest point, Stéphanie was living in emergency housing and eating at foodbanks. However, despite her reduced mobility and hearing impairment, in 2009, this single mother of 3 set up her consulting firm and went on to build a successful career in international strategy. 4 years ago, Stéphanie launched the Handiroad app and in 2019, Exportunity, with both initiatives earning her awards and recognition as an international incubator and growth specialist. She is dedicated to strengthening the legislation on disability and the French government seeks out her expertise on a regular basis.

Stéphanie thanked us for showing interest in her journey and for allowing her to speak safely. After years of suffering herself, Stéphanie’s purpose is to help those in difficulty who are still too shy or ashamed to open up. “It is thanks to initiatives like the ‘Iconic Alumni portraits’ that people like me can find the energy and the motivation to move forward.”

Where do you come from?

I was lucky to grow up in the 15th arrondissement in Paris, a place where culture was accessible and visible on every street. The UNESCO headquarters, an organisation that I have always admired, was just around the corner from my home.

What were the values your parents shared with you?

Frankly, they were too busy with their jobs to be overly preoccupied by our moral upbringing. There was an expectation for my two brothers and me to be independent and just get on with it. From a very young age, we went round with the door keys around our necks. My mother drew architectural plans and was always snowed under with work. My father was an architect.

You are a super-connected serial entrepreneur. Have you always been an extrovert?

Quite the opposite! Although as a girl my hearing loss was still mild, I was permanently anxious that I would misunderstand others, so I struggled to form bonds. I felt so different from everyone else that I preferred to stay in my bubble where I was less exposed. It was only in my thirties, after being diagnosed with Asperger’s, that I understood my behaviour better.

What were your coping mechanisms?

I struggled to relate to children around me and was much more comfortable communicating with people outside my family circle. I got on well with elderly and vulnerable people and wanting to understand their differences helped me to overcome my shyness. In addition, when I was about 10 or 11, I asked my parents for a subscription to the UNESCO Courier and Le Monde Diplomatique. These publications threw the realm of possibilities wide open for me with a range of exciting and culturally diverse stories.

Can you share the details of your disability?

I suffer from a neurodegenerative disease that affects the girls and women in my family. It affects my spine, ear canals, bones and cartilage. I have difficulties breathing and will have to undergo a series of operations to have my face reconstructed. I’m not sure yet what the new one will look like but it doesn’t matter! Luckily, my hearing only deteriorated gradually so my brain had time to memorise sounds. My voice is quite normal, although I don’t always realise when I’m shouting… fortunately my kids are there to let me know!

Luckily, once again, my high functioning Asperger’s syndrome has given me fast cognitive skills. My brain uses context and visual clues to help me fill in the gaps when I can’t hear. Interestingly, some of my disabilities compensate for the others.

How did you talk about disability in your family?

Disability was a totally taboo subject and no one ever mentioned it. My mother was ashamed of her hearing aids and kept them hidden from view and my aunt, who underwent 37 operations on her spine, was considered an embarrassment to our family. My grandparents hid her when they had guests.

At the time, we didn’t know that the disease was hereditary, so my parents didn’t connect my problems with the ones other members of the family had… or perhaps they didn’t want to. As a child, I felt incapable of transgressing this code of silence, so I bottled up my pain, my bouts of paralysis and my anxiety.

When did you get a proper diagnosis?

When I was 30, I asked my wheelchair-bound aunt to take me to the specialist who was treating her. The specialist told me very bluntly there was nothing he could do to stop the disease progressing. “You will end up like your aunt”, he said. That was a tough blow, but I must admit that since then, the dozens of other consultants I met have been helpful and empathetic. Some have even ended up crying in despair over my situation and prospects.

The disease generates lots of physical and emotional pain. I have never been ashamed of my hearing issues but it often bugs me to think that I waste people’s time when they have to repeat themselves. However, my decreasing motor abilities have sent me on a complicated journey of acceptation and renunciation. I used to dance and play squash, both of which I have had to give up. When you start losing your autonomy, it is not so much your pride but your sense of dignity that takes a hit.

What gave you this international focus?

My grandmother’s husband worked for Air France so I guess she could have travelled the world for free. Yet she never left her house for fear of access issues. I grew up surrounded by disabled people who refused to imagine the possibility of joy. I know that one day I will be paralysed and, like many of the women in my family, I may spend my last years in bed staring at the ceiling. However, I have consciously decided that I will discover the world while I still can, and make the most of my valid years.

What aspirations did you have when you were studying at Audencia? Did you write off certain careers because of your disability?

When I joined Audencia, I was two years younger than my peers and I firmly believed that the world was my oyster. I already had a clear objective of working in international strategy. Audencia turned out to be the ideal school to fulfil my thirst for knowledge and international dreams.

Socially however, I tried but never really managed to acquire the social codes, so I didn’t blend in and that was hard. I didn’t need a wheelchair back then, but I discreetly leaned on tables when my legs felt weak. My hearing was getting worse and there were gaps in my notes, but I never plucked up the courage to ask teachers and students to repeat themselves. I was a mute observer, stuck in a bubble. My inability to open up about my issues exacerbated my isolation. I still vividly remember one of the most traumatic days of those years. As always, I was sitting in the first row and intensely staring at the teacher so I could lip read. He must have confused my attitude with insolence, and in front of everyone, he asked me to stop. I felt exposed and ashamed but it was very much my own fault for not speaking out.

What was the turning point when you came out of your shell?

I had signed up to meet with recruiters at one of the fairs organised by the school and, thinking how important it was to be transparent with a potential employer, for once, I found the courage to talk about my disabilities. The feedback was bitingly dismissive: “You are young, you want to work in the male-dominated sector of strategy and you are aiming for international positions; how can you achieve this when you have trouble moving about and you struggle to understand people?! Unless you change your career plan, I can promise you 25 years of unemployment.” This was a huge slap in the face but also a powerful motivation to do something about my situation. I cried my eyes out until I realised that I hadn’t come all this way for nothing. I was determined to be even more convincing and gather more skills and knowledge.

Don’t get me wrong, there are still evenings when I cry after a physically and emotionally draining day. But the idea of rising up and giving things my best shot keep me going. I can’t afford to waste time standing still.

Did the first steps of your international career stand up to your expectations?

I had a blast! When I was just 21, the British IT company I was working for sent me to the CES in Las Vegas, the Mecca for tech. I had never done any public speaking, not even at school, and here I was on stage, facing 600 attendees. When I realised that none of them knew anything about me, I felt totally at ease, liberated and exhilarated. I soon took on more responsibilities and regions to manage. My role consisted in helping large foreign corporations penetrate and grow in the French market. My added value was to accompany them with intercultural management, helping their global teams to identify subconscious bias and work in better harmony. Fighting discriminations – whether against disabled workers, women in tech, or women founders, has been a red thread throughout my career. Sadly, 30 years on, we are still working through the same issues.

I later joined a large consulting firm, but there was no participative management, and the clients ended up leaving our strategy reports to die in a drawer. I realised I needed to put people at the centre of the strategy, and I launched my own international consulting company.

How did you handle the logistics of your business trips?

As much as I wanted this lifestyle to work for me, I ended up having to accept that travelling was physically and emotionally exhausting. Taxi drivers would drop me at the airport with my wheelchair and probably expected me to carry my suitcase between my teeth. When I attended professional fairs, I wasted a stupid amount of time trying to locate doors that I could open. Often, after a 6-hour trip, I would check into a certified wheelchair-accessible hotel, only to find myself stuck in front of a lift too narrow for my wheelchair. Frustratingly, there wasn’t a one-stop shop to help me with my planning needs.

Is this what led you to launch Handiroad?

Surprisingly, despite experiencing them first-hand, I didn’t realise straight away that I was bound to work on disability issues. The lightbulb moment actually came from my 5-year-old son, as he struggled to push my wheelchair across the pavement. It was physically challenging for him, he was fed up and he snapped: “Why don’t they make a Waze app for disabled people?”

I thought the idea was smart but I was a busy single working mum and I had already launched an incubator for startups interested in export. However, when I questioned my network, the feedback I received was overwhelmingly encouraging. The concept would serve my personal needs as well as those of the 25 million people facing mobility challenges in France from the disabled to the elderly but also parents with buggies for example… The Covid-19 lockdown period opened up people’s eyes about the stress induced by the lack of mobility. It affects our access to employment, health, entertainment… I realised that the concept was strategically innovative and that it would allow me to channel my passion for equality.

Can you pitch Handiroad for us?

It’s an app that makes moving about easier and safer for people with reduced mobility. In order to develop it at scale and in a cost-efficient way, I grew a community of users and I speculated on their kindness. Users help each other out by locating and warning about physical obstacles as well as aggressive behaviour they have been victims of. The four core values are kindness, equality, the power of sharing and joy. Joy is often underappreciated, yet it can be life transformative. I witness it every day, for example when grandparents can finally meet their grandchildren regularly.

“Universal Design” – a theory that aims for tools to be built by all and for all, is essential to my proposition. My consulting firm’s tagline was “make the world accessible to all”, which referred to the opportunity to expand to international markets. It also worked for Handiroad, so I kept it.

What gives you a sense of purpose?

I don’t sell glamour. I sell disability, suffering and stress. Yet I feel that by addressing these issues I can create hope. This is why I always jump at the opportunity whenever I am asked to speak in public. No one uttered a word at the last talk I gave but the following day I received 6,000 messages from people telling me they found me both inspiring and too intimidating to approach … the latter I find quite baffling!

From an external point of view, it seems that our society has become much more tolerant, especially in the workplace. What is your perspective?

Fortunately, the word disability is no longer taboo in the corporate world, even though we are still in an educational phase. Action is required now because I can assure you that there is still a lot of discrimination – enough to fill a book, or two!

When a disabled person is lucky enough to find a job, the role is often disheartening and ill adapted. I was once offered a telemarketing job selling mobile phone contracts – with my hearing impairment!

Moreover, the violence against us in the workplace is still real. Ten days ago, I was in a meeting with someone who wasn’t aware of my situation. I occasionally stand but as the meeting dragged on, someone in the room, who knew me, handed me a chair and explained to the guy: “She is disabled and it can be tough for her”. His reaction was “When you are a woman, and disabled, you don’t take on a job with responsibilities, you stay at home!” Comments like this can make you feel worthless but what was worse was the fact that no one else in the meeting spoke out. Sometimes these remarks are meant to be compliments “You know what? You’re actually quite smart!”

Being disabled and a woman is a double penance; in order to optimise my chances of raising funds, I have been advised on countless occasions to recruit a man as a business partner, “and if possible, a valid one”!

Four out of five women with disabilities are victims of violence in their daily life – whether physical, emotional, sexual, financial or professional. This injustice is close to my heart. So you see, dealing with other people’s attitudes is even more difficult than carrying the disease itself. I am lucky that I can now rely emotionally on a supportive network, but even then, it can get to you.

What would be your key messages to the Audencia community? How can we be better allies?

First, I want to encourage students who feel different to be brave enough to open up. You will be amazed how it will lift a weight from your shoulders, and how much more qualitative your conversations will become. On a practical level, I would like to make the teaching staff aware that with the multiplication of online events, subtitles are crucial. To alumni who are in hiring positions, I would say that when you receive a job application from someone with a disability, you should also see their potential for adaptability and innovation. When a new hire asks for specific modifications to their work environment and equipment, remember that they are not being fussy but that they have genuine needs.

People in HR should consider setting up inclusion workshops. I designed one for my clients where everyone is asked to work with a handicap for a day (blindfolded, with noise cancelling headphones, in a wheelchair…). This is a surprisingly cost-efficient way of creating awareness, promoting kindness and bringing a team together.

What is your proudest achievement?

This the sort of question that I never ask myself because I am eternally dissatisfied. Sometimes though, I look back and I realise I have done OK for myself in some areas. During lockdown, I entered an inclusion in tech competition with 114,000 female project founders from 180 countries. The first prize went to Microsoft and the second to me. I haven’t communicated about this prize, but it was such a powerful personal win. It brought me back to my childhood, when I was dreaming of the wonders of the world and believing that I would never be allowed to step in. I am proud to have designed a coherent itinerary and closed the loop.

![]() Reading Time: 10 minutes

Reading Time: 10 minutes

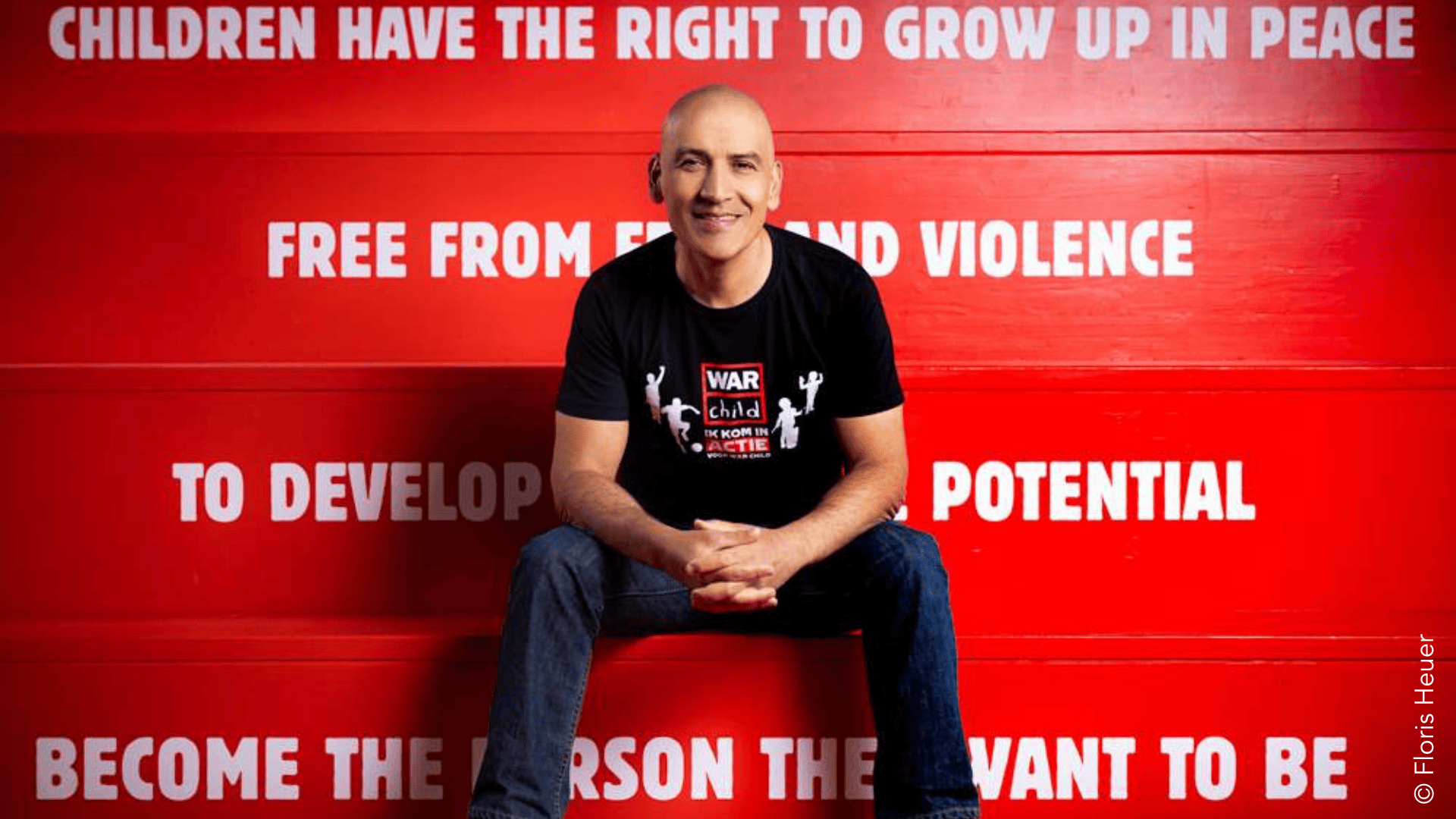

CEO War Child

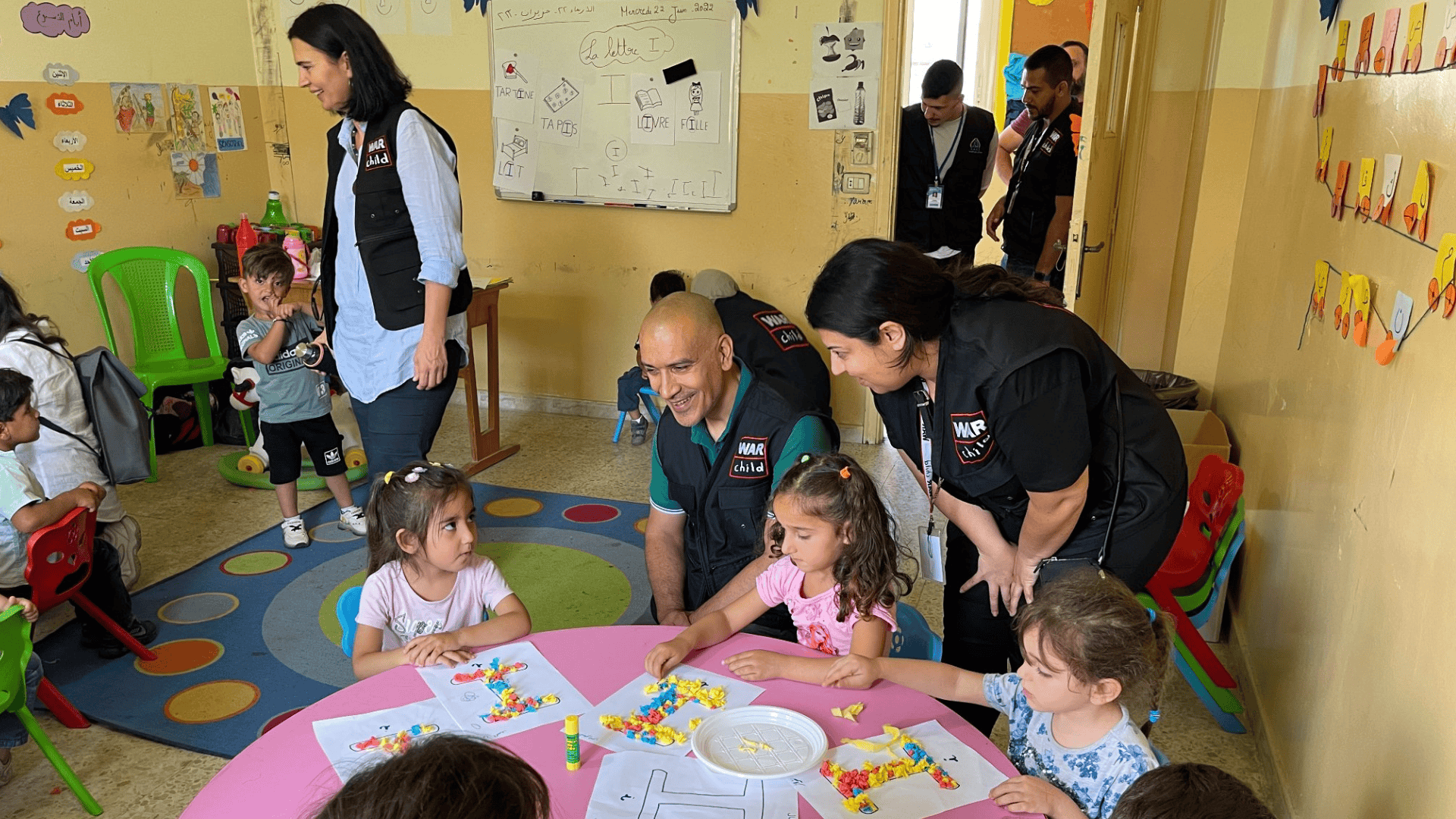

In 2021, Ramin Shahzamani was appointed CEO of War Child, an Amsterdam-based NGO that supports children affected by conflict around the world. Ramin, who has spent most of his career in the humanitarian sector, brings with him years of experience in international cooperation and fieldwork. He has been on the front line in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Colombia, Peru and Zambia.

In this brief presentation of Ramin Shahzamani, we mention no less than eleven countries. How else to describe the incredible international journey of a man whose career is driven by the desire to help the most disadvantaged?

Although he is realistic about the scale of the task - some 220 million children are affected by conflict around the world - Ramin is nonetheless fundamentally optimistic, an essential trait for working in the humanitarian sector.

You were born in 1970 in Iran; can you tell us about your childhood there?

The first eight years of my childhood in Iran were very normal and happy. I was a playful child sometimes getting into trouble but certainly enjoying life with my parents, brother and sister. My father was head of accounting and finance for Iran Oil, and my mother worked at home taking care of us.

From 1978, things started to change with the Iranian revolution. At first, it was quite fun because we didn’t always go to school and kids always like that! Then it became a bit more complicated because it was not a totally peaceful revolution. Our parents tried to protect us as much as possible and they did the best they could in a context where the changes soon had a radical impact on our lives.

How did you deal with leaving Iran at the age of 10?

Iran Oil’s offices were closed during the revolution. In 1979, the company asked my father to go to the UK to reopen the London office and we joined him there a year later. Then things got complicated for my family, and, without being too cryptic, my parents decided not to return to Iran but to head for Canada. I was eleven years old.

Arriving in London was tough as neither my brother nor I spoke English. We had to learn the language and adapt to a new culture in a difficult context: Iranian immigrants were stigmatised because of the Islamic revolution and the American hostage crisis. At the age of 11, you can already feel the discrimination. Children can be quite mean to each other and sometimes adults as well.

These events and major changes in a child’s life can shape their character, for better or for worse. Those years were important to me and certainly played a role in the decisions I made later on, giving me the desire to do something for the improvement of society.

What were the first years in Canada like and when did you consider that you had become Canadian?

For my parents at least, there was a lot of pressure. My father had a very good job at Iran Oil, and after he left, our lifestyle became more modest. Technically, we were not refugees, we had immigrant status, but in reality, the difficulties were much the same. However, my parents always placed an emphasis on education as the path to personal and professional success. As an immigrant, there was always a sense of having an additional obligation to succeed.

To be honest, the first three or four years in Canada were complicated, but things became easier once I mastered the language skills. I became more confident, developed friendships and started to feel like I belonged. Canada is a fascinating country for this. I always say I’m Iranian-Canadian and the beauty of it is that nobody questions it. I’m as Canadian there as anyone else and everyone considers me as such.

What kind of student were you, and what were your first jobs?

I think I was a pretty good student, but not outstanding. Like many teenagers, I struggled to find the link between subjects I enjoyed and what I wanted to do later. I really liked biology and microbiology, and later computer science, all of which were useful for my general knowledge but not directly for my choice of career.

After my first degree, I started an irrigation business with a friend I met at university. It was quite successful, but I realised that I needed other kinds of stimulation than the company was able to provide. My job lacked meaning and I struggled with this for several years before returning to university to get a degree in computer science. When I graduated, I could have gone to work in the private sector, but I had the opportunity to join a local NGO in India, as part of a Canadian government cooperation programme. That placement was my first experience of working outside Canada and it made me realise that social justice issues were at the top of my professional agenda.

So your time in India revealed your desire to be involved in the humanitarian sector

Absolutely. In fact, I have always been concerned with social justice and issues of peace and war in general. However, it was in India that I was first able to work in a structured way on social justice issues from a civil society perspective. After that, I applied for a job with the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy (WFM-IGP), a New York NGO. WFM-IGP is committed to the realisation of global peace and justice through the development of democratic institutions and the application of international law. I started out using technology for the communication purposes of the organization before getting involved in programmes, which clearly reinforced my calling to work in the humanitarian field.

I moved to the D.R. Congo to be the Country Director of the NGO War Child and my work shifted from human rights to humanitarian and development work, but of course, they are closely related. War Child’s mission is to provide support to children affected by conflict. In the D.R. Congo, I remained in the field of human rights, children’s rights to be more exact with practical programmes. For me, it was a great opportunity to work on projects that were making a real difference to people’s lives.

You have managed local War Child branches around the world. To what extent did you see suffering and how did you deal with it?

Suffering was certainly omnipresent and I saw it directly because I was living there. However, going sometimes without electricity or not having access to clean water are comparatively small hardships. You do observe true suffering and feel close to it but are not experiencing it directly. We are in these countries as foreigners and we work for organisations that have certain safety standards and take care of their teams. However, it is not unusual to be confronted with difficult security situations. I have been in some. In some countries, you are somehow close to the fighting that breaks out. You hear it and sometimes you see it. When I was in Afghanistan, the country was volatile and unstable. Some of our friends were killed. There were a lot of precautions to take. So you try to have mechanisms to deal with the pressure and the stress. For some people it’s doing sports for example. In D.R. Congo we could go swimming in the lake which was probably as safe a place as anywhere. That was not the case in Afghanistan, but we could still take a week off every now and then to get together with colleagues outside the country, to rest before coming back to our work. This was not the case for our local colleagues.

You changed countries several times. Is international mobility inherent to the humanitarian sector?

I spent almost three years in the D.R.Congo, two in Afghanistan and four in Colombia with War Child, then five years in Peru and two in Zambia for the NGO, Plan International before becoming CEO of War Child at the organisation’s headquarters in Amsterdam. It is common practice in the humanitarian sector to change countries often, at least for people who have careers in the field and who need to be close to the support programmes.

Contracts generally last between two and five years depending on the organisation and the security conditions of the country. This allows individuals to gain both personal and professional experience. The rotations allow organisations to bring in new ways of thinking and approaches to the field.

When you are in the field, you usually hear about upcoming opportunities before your contract ends. You can then express your interest to the NGO’s management, who will decide whether you are the right candidate when a new position and destination become available. Career development is based on opportunities and the match with your skills.

What made you decide to enrol in the EuroMBA programme?

Even though non-governmental organisations are not based on profit, their set-up is very similar to any other business. You have to generate income and develop products and services. You build teams, have a strategy and all the departments that any other company has. At War Child, we have a marketing department, for example. I’ve always thought it important to bring a business mentality and approach to the places I have worked. Doing an MBA helped me gain useful business skills. Most of the courses on the EuroMBA programme were taught remotely but we also spent a residential week in each of the participating schools of the consortium, including Audencia. I was in Afghanistan then and it was very intense, but I was able to devote time to coursework because it wasn’t like I had much of a social life there! Due to time and life constraints, I was late in handing in my dissertation, but I graduated – finally – in 2022.

What does your position as CEO of War Child mean in practice? What are your priorities?

We have been working on two major transformational and strategic changes for War Child. The first is to our structure where our guiding principle is to transform into becoming a network expert organisation. We want to move from a European-based organisation to a global, decentralised organisation where power will be shared between the different locations where we operate. Decentralising expertise, so to speak. This means giving more decision-making power to the local offices where the impact of our work is strongest. This transformation reflects an underlying trend in the humanitarian sector, where issues of equity and equality are prominent.

The second is to scale up our work and reach more children that need our services. War Child has developed real expertise in certain areas such as education, mental health, psychosocial support and the protection of children affected by conflict. Currently, our programmes have an impact on around 300,000 children per year, but according to the latest UN statistics, around 220 million children worldwide are affected by conflict. There is a big disparity between our impact and actual needs. To undergo this transformation, we need to develop more scientific, rigorous methodologies, not only to implement them in our own programmes but also to make them available to other organisations.

My main job as CEO is to drive the levers that will make these strategic priorities a reality. I have a great team pushing in the same direction and moving forward. Of course, we have to be realistic about the huge challenges we face because of the suffering of so many people in the world, but that doesn’t stop us from being optimistic that we can make an impact with War Child. My team and I are convinced of this.

How has War Child been able to respond to the needs of children in Ukraine?

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, more than 7 million children have had their lives – including their education – irreversibly disrupted. Displaced from their schools, homes and, in many cases, their country, children are experiencing unthinkable compounded learning loss; first from the COVID-19 pandemic and now from war.

In May 2022, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MESU) and the largest education non-profit in Ukraine, Osvitoria, approached War Child Holland to find a solution to reach and teach mathematics and reading to some of their youngest learners – children in grades 1-4.

War Child Holland took on this challenge and began the process of rapidly adapting its already proven Education-in-Emergencies programme, Can’t Wait to Learn, to meet these new demands for greater scale. This required a re-programming of the app to make it available – for the first time – on personal IOS and Android devices, along with its standard practice of co-creation and curriculum alignment with the government. Each version of the app is also uniquely designed with local children, educators and artists to reflect the culture, language and look of the country to make the learning experience for children feel familiar as well as fun.

In addition we are working with local partners to provide mental health and psychosocial support in protected spaces for children. These methodologies have also been scientifically proven to reach positive outcome for children.

What are you most proud of at War Child?

I’m really proud of the direction we’ve taken at War Child and the fact that we’ve put two big transformational changes on track. Of course, we’re still a long way off, and I’ll be even prouder when we’ve achieved those two goals. After all, we could have just carried on working the way we already do, but instead, we’re taking a pretty bold path to challenge ourselves and make these transformations: sharing our power and looking at what it really takes to expand our impact and reach millions of children.

Do you have children of your own?

I have a stepdaughter who is 22 now. She was with us in Colombia and Peru before heading to France to become a pastry chef.

What and where would you like to be in ten years?

I must admit that I don’t look that far ahead. Professionally, my goal is to complete my task as CEO of War Child.

What are you going to do with your weekend?

This weekend is my partner’s birthday. One of the things we’re planning is to go and see an art exhibition that’s on in Amsterdam at the moment.

I read that music is important in your life. Can you tell us what it does for you?

Music does play a big role in my life. Of course, I have my preferences, but I like all kinds of music. Each one touches me in some way. It can be a rhythm I like or certain lyrics I can relate to. Music is also very important for War Child, which is supported by many musicians and has been built using creative methodologies to support children’s mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Therefore, I have a personal connection and a kind of organisational connection to music. I listen to everything. This morning, for example, I listened to Lennon Stella.

![]() Reading Time: 10 minutes

Reading Time: 10 minutes

Life coach and reiki master

When we reached out to Henar Cabrera, she was living in Dublin and working as an International Customer Service Representative for Blue Nile, an American online jewellery retailer. Fast forward to our interview only two weeks later, and she had relocated to San Sebastian in Spain, and was proudly calling herself a life coach and reiki master. We got swept away by one of those conversations that seemed to take on a life of its own. Full of twists and turns, just like Henar’s life, in fact.

Growing up, Henar didn’t venture much further than her native Madrid, but her life changed gear the moment she understood she had to scratch that travel bug itch.

Audencia’s EIBM programme allowed her to lay the first stone of her international career. From Spain, to France, to Germany, to China, to Ireland and back to Spain, Henar’s journey is a travelogue as much as a story of professional transition and spiritual quest. A quest for healing from childhood trauma, for independence, for Mr. Right, for a purposeful job, and, above all, for finding her true self. Henar has come full circle and returned to her home country; along the way, she has found her mission, to motivate and heal others so they can live their best life. Full of wisdom, Henar’s words encourage us to soothe our mind and to trust and listen to our heart, the essence of our being and a reservoir of joy. They will inspire anyone who finds themselves questioning their life choices.

Tell me a little bit about your childhood in Madrid

It wasn’t all that straightforward, dealing with my childhood wounds; it took me years of therapy to accept that parents bring their own childhood traumas to the way they raise their kids, and that they did the best they could with the resources they had. As a child, I was an introvert, with dreams of a fulfilling life, imagining the full package: a successful career, a loving husband, and a house full of children. Now I suspect that those desires were in fact other people’s projections, rather than my own dreams.

Was the international career part of your plan?

The urge to venture outside my home country came to me quite late, with parents who were civil servants, I was raised in a very Spanish or local mind-set. The international seed started to grow after I went to study on a university exchange programme in Utrecht in The Netherlands. When I returned to Madrid, I got a job in TV news production for three years. I am aware of how glamorous that sounds, and I was grateful for the experience but at the same time, I couldn’t shake the feeling that it wasn’t my calling. I knew that something was missing, I craved adventure, I wanted to learn new languages and immerse myself in different cultures.

I was insecure about this dream for a long time so I decided to go abroad again to study, thinking it would give me the confidence and the foundations I needed for an international career. When I discovered Audencia’s European and International Business Management programme, it felt like the absolute right path to take.

What appealed to you about the EIBM programme?

The programme consisted of a rotation every three months in three different countries: Spain (Bilbao), France (Nantes) and the UK (Bradford), which I found particularly exciting. It focused on international business with a solid curriculum in international law, finance and human resources. However, to be honest, I picked this programme primarily for the international opportunities it offered.

Unlike many students, I had no preconceived plan when I enrolled. I admired and, at times, envied those rational and determined people, and blamed myself for my lack of direction and confidence. I am much gentler with myself now, because I recognise how much of a leap of faith this move had been for me. Today I know myself better and I accept that intuition and spirituality drive me more than rationality.

Did the programme fulfil its promise?

The curriculum was heavy on numbers, which overwhelmed me for the first few months, especially as I was studying in a different language. However, I surprised myself with my ability to hang in there despite the difficulties. I felt encouraged by a strong force, which I can only attribute to God. I was not at ease with the networking aspect either, but I knew that it was an essential part of the experience. I pushed myself to connect with the other students and gradually it felt more natural. In France and Spain, my timetable was quite dense. At Bradford, the schedule was lighter with more assignments than contact hours so this gave me more time to socialise. This was how I met the man who took me to China…

Tell us about your professional peregrinations

I found a job in Paris; which I don’t think I would have managed without my experience in Nantes. It was a blissful time, working for Windrose, selling documentaries and other TV content all over the world. It was the perfect way to combine my media background with my international business skills. The French community accepted me as one of their own. I was lucky to attend high profile events such as the Cannes International TV market and it was gratifying to realise that I had become comfortable with networking. It goes to show that you can always develop your ideal personality type. I recall one evening in Cannes, when we celebrated a friend’s birthday: she was Russian – we’d met in Spain – and we partied with interesting people from all over the world. I felt in total harmony in this international environment, as if the stars had aligned for me.

When my boss took on a role in Germany, she suggested I go with her and I accepted in a heartbeat, excited to step into yet another universe. However, after a few months, the workload and the stress had become so unbearable that I one day I suffered a panic attack in in the office. My inner awareness kicked in again and pushed me to extract myself from this unhealthy situation. I realised that my curiosity was tempting me to explore even further. By a strange twist of fate, my boyfriend at the time – with whom I’d had a long-distance relationship for several years, had just decided to return to Taiwan where he was from so I upped sticks and went with him. The administrative formalities to obtain a visa were frankly a hassle but then Swedbrand, an international packaging company, recruited and sponsored me. I enjoyed some business trips in Europe, however I pushed myself to reach my sales target at the cost of my own wellbeing again. Then in 2016, I got a job as a customer service representative at Blue Nile, an online jewellery company, and that position was such a blessing.

So what led you to coaching?

After suffering from work-related anxiety for many years, I finally found working environments in China that made me feel at peace. I was in the right state of mind for some introspective work, and this is how I discovered my interest in coaching. I realised that my friends often came to me to share whatever challenge there were going through, and I was naturally a good listener. I started to believe that I could leverage this trustworthiness and make a career out of it so I enrolled on evening classes in coaching and stepped into a close-knit community. This was a wonderful and balanced phase in my life: my daytime job provided me with an international outlook and stability and in the evenings, I was exploring this new activity that made me feel so alive. I started organising motivational and self-development workshops as a freelance coach. I was amazed to have found a path that I could build with my own hands and which gave me so much joy.

Why did you move back to Europe then?

The relationship with my now ex-boyfriend didn’t work out. With hindsight, I could have predicted that before moving to the other side of the world with him, but I don’t have any regrets. I had to go through those experiences to gain self-awareness. So, I found myself single in China where I felt settled, with a job that I liked, a supportive friendship network and this fulfilling passion project with coaching. Nevertheless, I was craving a relationship; I continued dating, but I had a feeling that I would find love in Europe. I remember going to Spain for the summer holidays and realising how lovely life was in Europe. I decided that a new lifestyle was within my reach and that I should move while I was still young and unattached. My employer, Blue Nile, had a European base in Ireland, and they were happy to transfer me there.

So was Ireland the place that finally ticked all the boxes?

Not quite, but here’s a scoop! I found my true love and life partner in Ireland, and we are engaged to be married! I also certified as a life coach, which is a proud achievement. My corporate life, however, felt unsettling again. My sales targets had increased, along with my stress levels so one week ago, I resigned from secure employment to embrace my soul mission. I hadn’t imagined that my transition towards coaching would be so radical and sudden. My initial plan was to build a secure client base before moving into coaching full time, but there was a point when I felt totally bogged down. Carrying out both activities in parallel became difficult because my corporate job was demanding for my brain, and when I coached it became difficult to shift my focus to my heart and guts. I am grateful to my employer for their trust, but I have accepted that for me there is something more to life than a 9 to 5 corporate job, which suffocates my soul. Today I am ready to spend more time being closer to the unknown and the uncomfortable, until I figure out the next stage of my life.

Congratulations on the upcoming wedding! Where is your fiancé from? Ireland? China?

Ha ha! He’s Australian actually! He teaches English and we share the same passion for discovering other cultures. If we add up the countries that we have each lived in, it comes to 13! We met in Ireland and he’s the one who felt the urge to relocate. He was craving the sun and the sea and he found a job in San Sebastian. He has offered to support me while I set up my business and I trust him in his knowledge of what is best for the two of us. So I have moved back to Spain out of love for him and this is how I have reconnected with my homeland after 12 years away.

So have you managed to align with your life purpose?

I am definitely on the right track! I coach people in finding and planning for what they truly desire. I am also a reiki master; the objective is therapeutic, it’s about helping people to heal from past trauma, so they feel in harmony with the present and themselves. And since I am passionate about relationships and dating, I also offer what I call “Eat, Pray, Love” coaching. Some women -including me, have been struggling with toxic and even abusive relationships. They get caught up in the same pattern, which often also affects their professional relationships. I am here to support women navigating through a breakup, healing a broken heart, returning to the dating arena, and forming a sacred union. All these disciplines can be powerful tools to make the most of this one short life we have.

Do you regret your past educational and career choices or even see them as a waste of time?

I have no regrets whatsoever, I have been figuring out my life as it’s been unfolding. It took me these long exploratory phases to accept that corporate life is not for everyone, despite the remarkable comfort and security it brings. My parents still struggle to understand my choices but I know that the pressure that they still put on me to achieve their version of success comes from a good place. I value their opinions, but I am now much better at following my own desires.

Are there any recommendations you would like to share with Audencia students and alumni who are currently trying to figure out their own personal journeys?

As a life coach, I don’t like to give advice. I know that people have to figure out their own journey. What I am certain about is that fulfilment starts with being aware of the expectations that others have for us – our parents, friends, teachers, etc. Then it’s about connecting with our heart; our heart is wiser than the rational model we have been taught to follow. My recommendation is to listen to what you truly desire beyond all those social projections. A heart-centred and joyful life is much more empowering than the false sense of security provided by the logical and capitalistic world we live in. I know that the process can be terrifying, but trust me, once you take that leap of faith, the doors open.

You have mentioned God several times. Have you always been guided by spirituality?

I was raised a Catholic but as an adult I disconnected from my faith. I remember, aged 28, when I was living in Germany and had just returned from visiting my now ex-boyfriend in the UK. It was freezing cold, I was walking along the street, my arms loaded with grocery bags, and I was missing my boyfriend. Sometimes living abroad can feel very lonely. I came across a church and I will never forget the feeling when I stepped inside of being hugged by God. Reconnecting with my religion has helped me tremendously in overcoming all sorts of challenges. On days when my sales results were miles away off target and my stress levels were through the roof, I would find comfort in the Bible. Did you know that in the Bible, the phrase “Don’t worry” features 365 times? I now ask God for guidance at each important step.

It might be a difficult question because you are in the middle of another transition, as you have just moved to a new city, are about to get married and set up your business, but, do you have any idea where you would like to be in 5 or 10 years’ time? What do you wish for yourself?

What I truly desire is to be able to earn a living in a way that is in synch with my soul, using my talents for a higher purpose, to serve the community, to touch others, to be independent and to create wealth from within.

Is there anything that you are looking forward to doing this week?

I have been away from my fiancé for a couple of months so I can’t wait to see him. I am also looking forward to my regular running session along the esplanade. Running gives me the opportunity to leave my problems behind for an hour, and feed my soul and body with mindfulness and endorphins. Watching the sun come up while you are jogging is a beautiful way to show gratitude for the gift of life and to start the day with intention!

![]() Reading Time: 9 minutes

Reading Time: 9 minutes

Professional rugby player

Fulgence Ouedraogo is the tireless tackler and captain of the iconic Montpellier Hérault Rugby Club, in the South West of France. Loyal to the club where he started as a pro, “Fufu” has been described as a role model and the soul of Montpellier. In 2011, he led his team to the final of the Top 14, the French professional rugby union club competition… gritting his teeth to ignore the pain of a broken hand. His international record is equally impressive. He has participated in several Six Nations tournaments (in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2013), won the Under 21 World Cup Championship, and faced the mighty All Blacks in the World Cup final in 2011.

With a height of 1m88 (6’2”) and weighing 99kg (15.5 stone), this gentle giant is highly respected for his integrity and bravery. Learning about his challenging start in life sheds some light onto his special qualities. Born in Burkina Faso, his parents sent him on his own to France when he was three, to be raised by a foster family. They hoped that this upbringing would give him access to a better education. Against all odds, Fulgence has pursued an exceptional sporting journey and he is grateful for how fulfilling his life has turned out to be. But he is still battling with unanswered questions around the merits of his parents’ decision. The athlete refers to rugby as a school of life that has helped him to take control of his destiny equipping him with crucial skills on and off the field. In 2017, in anticipation of his post-sporting career, Fulgence enrolled on an executive education programme at Audencia that he successfully combined with his intensive training regime.

Fulgence shares with us his efforts to make peace with a troublesome past, his passion for the noble sports, and a few of his favourite pleasures as a father raising young children in the countryside.

Do you remember the day that your parents sent you away?

My earliest memories start when I was 4 or 5 so I have no recollection of the separation. After my older sister died, my parents decided to send me to France; they wanted to offer me the best possible chances of a good education. In their mind, I would return to Burkina Faso after my studies. But my life has taken a different turn from the one they had predicted. My father, a primary school teacher, was in touch with a colleague in France who facilitated my transfer to a host family.

I have read that the initials of your mother, brother and sister are tattooed on your shoulder. Is this a sign of forgiveness?

To this day, I still have so many unanswered questions such as why I was the only sibling that my parents sent away. The lack of answers troubled me during my childhood and I struggled to find my place and to grow without the comfort of knowing where my family nest was. Especially now that I am a father, and even though I know that my parents had good intentions, their decision is hard to accept.

I had limited connections with my parents, my brother and my sister who all stayed in Burkina. But on reaching adulthood, I made a conscious attempt to discover my roots. Reconnecting with my family members hasn’t been easy because I don’t know them well and we have never shared any intimate moments. Nevertheless, despite all that has happened, I believe that the emotional links between a mother and son are indestructible and I am glad that we were back in touch. My mother passed away in 2015 when I was preparing for the World Cup and the last time I went to Burkina was for her funeral.

There is no doubt that had I stayed in Burkina, I would never have had the same career. But even more now that I am a father, I appreciate how growing up among your relatives gives you solid foundations. Anyway, there is no point in dwelling on life scenarios that I had no control over. However challenging my childhood was, it made me into who I am today.

Tell us about your childhood and how you got into rugby

I was raised in a village near Montpellier, steeped in the traditions of south western France. I only have the colour of my skin from Africa; I don’t speak the language and I haven’t mastered the cultural codes. Rugby wasn’t a traditional sport in my foster family; they had actually planned to sign me up for tennis lessons, but the club didn’t have enough members to open, so rugby was plan B! I started playing at the age of 6 in a small club near our village.

I am quite shy and have always been rather reserved. For me rugby was primarily a way of having fun with my friends and letting off steam. As a child I didn’t even think of becoming a professional rugby player; I wanted to be a fireman, then a lawyer! But from the age of 16-17, my performance improved rapidly. Our coach identified my potential, I moved to the Montpellier Club, and this is when I first started to dream about becoming a pro. Before I turned 19, I was selected to join the French team and soon afterwards, played my first game with the pros in the first team. In under two years, I went from playing in my little local club to representing my country in international competitions, which was quite surreal. I have remained grounded, thanks to my friends who came to cheer me on at the big games.

Years of success ensued. What are some of the most emotional moments you would like to highlight?

It is hard to pick just a few, but I would go with my first game in the first team for France because it felt such a special privilege. Then the whole of 2011 was memorable. I participated in my first Senior Rugby World cup and we played the final against the host country at the legendary Eden Park Stadium in Auckland. After the national anthems, the All Blacks performed their traditional haka and we decided to respond by staring back and advancing towards them in a V-shaped formation. We suffered a narrow defeat but this match is etched in my memory forever.

You were very young when you were entrusted with the captain’s armband. How did you manage this responsibility?

I had been captain of Montpellier’s 1st team but it was a still shock when I heard I had been named captain of France’s U21 team. Many of the players in the team were professionals with more experience than me, and some had played on the international stage. It was daunting at first, but I learnt on the job. My style consists in leading by example rather than through longwinded speeches. I insist on flawless behaviour in training as well as during matches. This is how I earnt my legitimacy.

There is a unique ethos in rugby. What makes you so attached to the game?

From the very outset, I have had the privilege of being trained by exceptional coaches who shared their passion for the sport and its values: discipline, respect, integrity, and solidarity. These values build character and transcend into everyday life. Rugby pitches are often where lifelong friendships are forged. It is well known that I am inseparable from Francois Trinh-Duc with whom I have been lucky to follow a similar progression, from our little club at the Pic Saint-Loup, all the way to the national team. But I still count many other of my childhood teammates as my closest friends. As adults, we have all turned out as well-rounded citizens.

Where does the nickname “Captain Courage” come from?

In 2011, I fractured my metacarpals in the semis of the Top 14. It hurt like hell, but there was no way that I would have missed my club’s final a week later. So I strapped my hand tight and bit the bullet! It was not my most serious injury, but it’s the one that people have most commented on, and the one that earned me that nickname.

How have you managed the most challenging phases of your sporting career?

My shoulder injury in 2013 was worrying. I underwent surgery and I contracted a nosocomial infection in hospital. I had to go back to the O.R. a month later, and returning to the pitch was really tough. Difficult relationships in the club, disappointing personal and team performances affected me mentally. As I am not the type of player who easily opens up, I could only rely on myself. The easy way out would have been to quit but I am a man of passion and challenges motivated to train even harder.

In 2017, you enrolled on an executive education programme at Audencia (DCP*), presumably to prepare your post-rugby years. Is it a programme that you would recommend to other sportspeople?

2017 was a pivotal year on many levels for me. My partner and I moved house, and our son was born in January 2018. Fatherhood changed my priorities, and I felt a stronger sense of responsibility. For the first time, I seriously started to project myself into my post-rugby life. I wanted to be equipped to anticipate my career shift. I signed up to a skills assessment programme and decided to retrain. I found the Audencia programme appealing because its solid curriculum including accounting, HR, negotiation and finance, would give me the keys to a variety of projects. In addition, the remote learning possibility was particularly suited to my heavy and unpredictable training schedule.

*DCP [Director of a Profit Centre] is 9, 12 or 15 month programme, in French, offered by Audencia Executive Education

But going back to school was testing! I was coming home drained after a day’s training. I was often alone with my baby so I had to put him to bed as early as I could to start studying. Most of the students in the programme had some knowledge of management as well as some business experience. For me, this universe was totally unfamiliar. I felt so behind and initially I had to google definitions which seemed straightforward to the others. I resorted to asking my peers for help… that was quite a first for me! Luckily, my classmates were great, understanding, and supportive.

It took a lot of resilience but I am proud to have persevered. The programme gave me the vocabulary, the contacts, the mindset and the confidence to start a business venture. I would recommend this formula to other sportsmen, but I would just warn them that the experience can feel isolating so it requires self-discipline. I only came to the Nantes campus once, for the graduation ceremony. There was a great atmosphere that day. We were all so happy to meet each other -at last- in the flesh, and some students even queued up to ask me to sign autographs!

I started the programme with a few ideas in event management, and I refined one during the year. Then Covid threw a spanner in the works. I am now working on another one that could work via video. More will be revealed later…

What does a typical working day look like for you? And a “down day”?

On a training day, I usually leave home at 7am. We start with some stretching, a warmup, and exercises to test our fitness level. We have breakfast together, and this is followed by a video session, a weight workout, the first training, then lunch, another video session, another training, and the post training video session. We finish off with stretching, physio and balneotherapy. I don’t get home until 6.30pm. So you see, the regime is more intense that many people realise! I like to spend as much of my downtime outside as possible. I was raised in the countryside, I love fishing and tending to my vegetable garden. And spending some quality time with my family, close to nature.

What brings you purpose and meaning in your everyday life?

My children are 2 and 3 and I am concerned about the environment we are going to leave them. Our planet is precious and I try to teach them what can be done at our level to protect it. I am far from a perfect environmentalist, but I focus on sharing with them life’s simplest pleasures. I show them the little gestures that create attachment to the natural world. I want them to understand the importance of respect and compassion. When my kids come back from nursery, the first thing they ask is to get the eggs from the henhouse, to pet the rabbit and to pick raspberries. Nothing makes me happier.

Where do you see yourself in 5 or 10 years?

I am actively reflecting on this. I hope to still have 1 or 2 seasons of rugby ahead of me. When this is over, I might relocate, even maybe abroad to experience another culture, but nothing is set in stone yet. As for deciding on my future professional adventure, I know it will be difficult because when you have lived off our passion all your life, it’s hard to imagine a project that will be as motivating. I doubt I will ever be able to re-live the same intense sensations that I have enjoyed on the playing field. But I will still look for a role that can provide me with emotions and pleasure.

What are the two black and white photos hanging on the wall behind you?

One is a picture of me as young boy having a whale of a time on the pitch with my friends. The other is a portrait of Mohammed Ali in the ring. He is the ultimate embodiment of discipline and mental strength, and an icon to many athletes.

![]() Reading Time: 12 minutes

Reading Time: 12 minutes

MULTICULTURAL LIAISON OFFICER

Amal hesitated before agreeing to an interview for our iconic alumni series. “I wasn’t sure that my profile would be a good fit because my story is messy, with some ups, but also lots of downs.” She came on board when she realised that it would allow her to look back on her odyssey and document her journey to date. Amal’s itinerary has taken her from Yemen to Malaysia, the USA and now Canada where she new works for the immigration services organisation, which assists newcomers. Raised in conservative Yemen where girls were destined to marry early and become housewives, Amal’s career has been admirable; it is the desire to make a difference that has driven her from a young age.

Against all odds and facing objections raised by some of her relatives, Amal went into higher education thanks to prestigious “high potential” scholarships and came out with two master’s degrees. With a war-torn country as a backdrop, she studied for an MBA at Audencia, then returned home to hold a high-profile role in the (later aborted) peaceful political transition process, later being hired by the UN. Amal’s journey is a testament to her strength of character. We have grown accustomed to narratives where the selfless hero is rewarded with a happy ending. But Amal ended up in exile and recent years have proved bittersweet.

Amal’s life, like that of millions of other migrants, outstrips fiction. We are profoundly grateful to Amal for sharing it with us.

What is your family background?

I am the eldest of five siblings and was born and raised in Yemen. Both my parents were educated and open-minded, which was an exception to the norm in such a poor and traditionalist country. My mother had dreamt of becoming a businesswoman or economist. She married my father – then a student but later a financial General Manager – when she was still in high school. At the time, it was uncommon to see women in higher education, but my father supported her and she got a degree in economics and political science from the Faculty of Business and Trade. My mother was determined to work, even as a teacher, not just because she valued self-worth and independence, but also because she wanted to join forces with my father to provide us with a quality of life which included receiving a private school education.

What were you like as a child?

We lived with my extended family and I can still hear the laughter echoing through our compound. I was the eldest of 13 cousins, and I emerged as the natural leader of my pack. My grandfather and my father were very fond of me and proud of how mature I was. When I was nine, they started to confide their concerns to me, and to involve me in decisions affecting the family. From my childhood, I recall a feeling of freedom and innocence, as well as a sense of pride for contributing to the family’s important matters. I am grateful to have had the chance to grow in confidence and deal with responsibilities, as this helped prepare me for the hardship to come. I was 27 when my father died, and I naturally stepped in to support my family financially and emotionally.

Adolescence is an important transition for girls in Yemen as they are separated from boys. How did you live through this phase?

We used to be in mixed classes, school was fun, and I was a joyful and talkative child. My parents being open-minded, I had the privilege of being allowed to play with boys after school. But when I turned 12, I was made aware of how my body was changing, and suddenly I was considered a woman. Society expected us to “behave like ladies”, which included wearing the hijab, refraining from being loud or laughing demonstratively, and being assigned a “male guardian” who made decisions for us. I was prepared for this rite of passage, but I still took this attack on my way of life and freedom as a cruel injustice.

You wanted to become a doctor, … is it not a boys’ dream in Yemen?

Ever since I was a child, my nickname was “Doctor Amal”. I always achieved good grades and in Yemen, the royal road for high- performing students is to go into engineering or medicine. I wanted to become a doctor because I thought it would be the best way to help vulnerable people. And also, because the rebellious side of me was desperate to prove to everyone – and to myself, that I could succeed in a field that was traditionally a man’s prerogative!

My way of coping with how I was treated as a teenage girl was to turn in on myself and to focus entirely on my education. I became quiet, introverted, lonely … but it paid off.

When I finished high school, my parents received lots of marriage proposals. 17-18 is the peak age for marrying i.e., for getting protection and economic security. My mother supported me in my decision to finish university first, against the objections of some of my family members. My life could have taken a whole different turn if it hadn’t been for my mother, my father and my grandfather who understood and respected my decisions.

I worked extremely hard for the medical school’s entrance exam. My parents were so proud when I got a place; I specialised in pharmacy. My social life was poor as I was obsessed with succeeding academically and became competitive. I hid my femininity because I was not comfortable when people complimented my looks; I wanted people to notice my mind.

Once a qualified pharmacist, you made the brave decision to give your career a completely different turn. What was the trigger?

In my third year at uni, I attended a Youth Development Conference (YDC) organised by the Canadian-Yemeni Collaboration to empower young people to set goals, build self-confidence and network. Meeting some fascinating speakers and activists and interacting for the first time with people from abroad created a shift in my personality. The nerd that I had been for years had a lightbulb moment: I could be a dedicated scholar whilst connecting with people. The joyful and outgoing personality that I had as a child started bubbling up again and I came out of my shell. I started to volunteer for different NGOs and get involved in the community.

A couple of years later, I realised that working in the pharmaceutical industry was the wrong path for me. I wanted to work in a lab and invent new treatments to improve people’s lives but had ended up in a sales role instead, in which, as a woman, I struggled to be taken seriously by my clients at that time. More importantly, I didn’t feel I was adding any value. I accepted that just because I had studied hard for five years did not mean I had to stick with this career for the rest of my life.

Announcing to my parents that I was moving to the nonprofit sector was not easy, but they trusted my decision. I started coordinating health, education and human rights programmes, and was rapidly promoted to project manager: I had found my calling.

Why did you decide to join Audencia?

At 30, after 5 years in the field, I decided it was time to try to fulfil my dream of studying abroad and discovering the world (here I was applying in secret so no one could hold me back). Only a handful of prestigious scholarships are accessible to Yemeni students, one of which was for an MBA at Audencia, funded by Total. The selection procedure was tough, and the process was intense, especially as it took place in a tense political context. In 2011, all the main institutions shut across the country because of a popular uprising. So, Total had to send us to Cairo to take the GMAT test. I flew back home and the airports closed a day later. But I made it and was offered a place!

To be honest, France was not my first choice because I didn’t speak the language, I had no relatives there and I had heard rumours that the principles of secularism in France marginalised Muslim girls. But I knew that this was an opportunity worth seizing. I announced the news to my family whereas no one was even aware that I had applied. As I expected, objections started pouring in: “How are you going to travel? You need a male companion! You won’t be welcome there!” My mother was anxious, but her pride took over and she let me go.

You say that your experience at Audencia was “life changing”. Can you tell us why?

When I arrived in Nantes, I found myself completely on my own, which had not happened in a long time. Finding the right outfit was daunting. I was wearing abayas in Yemen, a full-length garment that only let my eyes show. I knew I had to find a compromise between a modern look that western people would accept, and a modest one in which I would feel comfortable. I had decided that if I was ever asked to take my hijab off, I would fly back home. Luckily, in private institutions, the rules on religious garments are more flexible than at public universities. Yet, exposing my face was a huge step; I felt naked for the first few months.

At first, I was anxious about some of the social norms, such as handshaking. Then, on observing my Japanese classmates bowing, it was comforting to realise that I was far from being the only one with different cultural habits. One day at the beginning of the year, we were joking around in the class and a girl from Asia told me that she had never realised that a Muslim girl could laugh and be friendly! Initially I was shocked and a little insulted, but we ended up forming a beautiful friendship and years later, I even stayed at her home in the USA. Our MBA class was truly international, and the staff at Audencia were always mindful of cultural considerations which, over time, helped me feel less awkward. We became each other’s second family and social network, and we all gained cultural understanding.

Yes, my time at Audencia was literally life-changing. I developed confidence and clarity as regards my career aspirations. I also let go of any preconceived ideas I had about western culture. I realised that I should stop seeing the world through the eyes of my community, or the media, and start applying my own filters.

What are your best memories from your time at the school?

Academically, I worked at merging my interests in community empowerment and social development with my newly acquired skills in business management. I discovered the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility and based my graduation project on it.

During school breaks, I had an amazing time with my classmates on various trips to Belgium, the Netherlands and Spain. Our travel style was so different from the Arabic way, which is all about comfort and safety. I had so many “firsts” on those trips: learning how to use a paper map! Travelling by train! Spending the night in a sleeping bag! Foodwise, I became increasingly adventurous: I tried sushi, and dare I admit it … even snails!

You have held prestigious roles in Yemen, tell us about them

I returned to Yemen just as an agreement was found to enter a peaceful phase of the National Dialogue Conference to prepare a new constitution. At that point, I was well known in the nonprofit sector and had an MBA from a respected business school in hand; I quickly obtained a role as head of the Community Participation Unit in the General Secretariat of the historical conference that took place from 2013 to 2014. Basically, I was in charge of giving voice to the voiceless in our society to promote the dialogue: women, youth and NGOs. It was the highest position I had ever held. The work of the General Secretariat was directly connected to the president of Yemen, and I dealt with the political leaders as well as the United Nations special envoy. It was also the most fulfilling post, as it was an opportunity to contribute to the new Yemen.

After that, the United Nations hired me to manage a communication platform that they had set up to allow independent groups to communicate, which was another highly rewarding role. Tragically, conflicts erupted which sounded the death-knell of the peaceful transition. At the end of the day, things were out of our hands.

Can you share with us the conditions in which you had to flee your country?

In 2015, the bombings intensified, and the conflict turned into a ruthless and traumatic war. I was determined to get my family out of the country. The UN invited me to attend a peace conference in Geneva, but no one except UN staff was allowed to board UN planes. Leaving my family behind was not an option for me and, with the Saudi coalition having bombed all the airports, I resorted to organising a risky bus trip to Oman for my mother, my siblings and I. From there, we flew to Malaysia – a country where Islam is the official religion and where I thought we would be safe.

We ended up staying for six frustrating months, with little or no visibility on how events were going to pan out, and our savings were gradually dwindling away. I had gone from holding a prominent UN role with exciting prospects to being stuck in exile.

One day, however, I received some unexpected news. I had been accepted on a master’s programme, in international development in the USA, that I had applied for the year before. The scholarship was only awarded to four participants and I was the only woman! I was stunned but also conflicted, in light of the unstable political situation at home. My mother eventually persuaded me to go. She reminded me of how hard I had worked to earn this scholarship. She told me: “The UN has put an end to your contract, so you have no reason to come back home. You have supported the family since the death of your father and your siblings are almost all grown up. Now is the time to think about your own future. Don’t miss this chance”. It was the first time my mother had expressed her appreciation so openly to me.

I flew to the USA to pursue my dream of enhancing my education, wracked with guilt, as my family returned to Yemen where their lives were going to be at risk. Still to this day, I often regret my decision, since it led to my not being able to see my family for five years.

Tell us about your experience of being a Yemeni woman in the USA under the Trump administration?

My plan was to complete my master’s at Ohio University, then return to Yemen and be in a stronger position to contribute to rebuilding my country. But the war still hadn’t ended; it still rages on today. There have been times when I’ve been desperate to go home, especially when my grandfather fell ill. However, my family has always categorically refused to allow it, arguing that millions of Yemenis are trapped in hell and that I should not compromise my own safety. Instead, I’ve tried to find ways of making myself useful by working and volunteering at the university to help international students adapt to the local life and American culture.

Then, the newly elected U.S. administration imposed restrictions on Yemeni citizens. If I were to leave the country, I would risk not being allowed back in, thereby losing my scholarship. I missed a job opportunity because of my nationality: the recruiter was concerned that the ban on Yemenis would make recruiting procedures too complicated. Yet the project consisted in helping Yemeni communities … and they recruited someone from Egypt! For me, this entire situation was both unstable and unpromising. After so many sacrifices, I felt unwelcome and stigmatised. I fell into depression and I knew I had to leave.

How did you ended up making a new life for yourself in Canada?

I had a few relatives there. Moreover, the country has a “Yemenis Welcome” policy and recognises Yemeni citizens as victims of war, like Syrians. It had never been my plan to settle in Canada, but life does not always work out as one expects. I just had to accept my fate, and learn to live with the consequences of my choices. Back in 2013, I thought I was in such a great place, surrounded by my loved ones, good qualifications, my dream job and a network. I had to start all over again in a new community.

I now work as a multicultural liaison officer, helping refugees and professional migrants to settle and integrate. I assess their needs, guide them towards any relevant resources, help with translations, and educate them on cultural differences. This job makes me happy. Once again, I get to experience that rewarding feeling of making a difference. I have gradually built up a new social network, I go out, I try new sports, I travel… throughout Canada.

What is your biggest wish for the future?

My immediate goal is to try to bring my mother and siblings over here to Canada, which has now become my second home. My long-term plan is to help Yemeni people and to visit Yemen again one day. I know that it will take years because there is no solution in sight to the end of the conflict. It has become a hugely complicated geopolitical issue and currently constitutes the world’s largest humanitarian crisis. My younger brother is 12, and he too, just like all Yemenis, deserves better. My life is no more valuable than anyone else’s in Yemen, but I refuse to become just another number to add to the list of casualties.

My wish is to make my mark on the world, wherever I find myself. My purpose is to help those less privileged to get the decent life they deserve.

What are your daily coping mechanisms at overcoming despair and frustration?

My job brings me purpose and comfort. I keep in touch with my family and we cheer each other up. My philosophy is that nothing lasts forever, whether it is happiness, sadness, or hardship. I believe in karma and that better days will come. I also try to look back and appreciate the progress I have made: I arrived in this country feeling like a victim who had no plan and no control over her destiny. I now have a career, new friends and what’s more, I have allowed myself to dream again.

What are your plans for the weekend?

We have a bank holiday weekend coming up in Canada for Thanksgiving. After talking to you, I will jump straight into a Skype call with one of my ex-colleagues in Yemen. I love a good catch-up and it’s important for me to keep connected with my network back home. Then I’ll go for a long walk in the park, to absorb the vibrant colours of Canada in the fall. There’s nothing quite like it!

![]() Reading Time: 11 minutes

Reading Time: 11 minutes

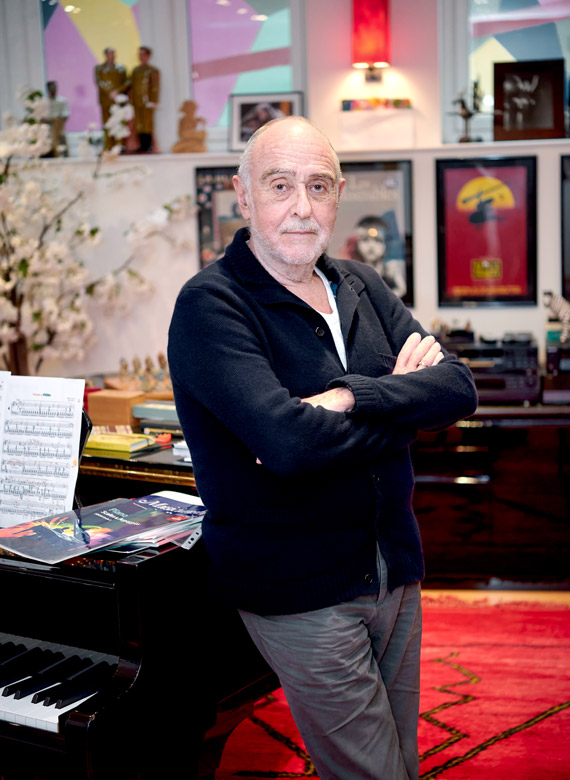

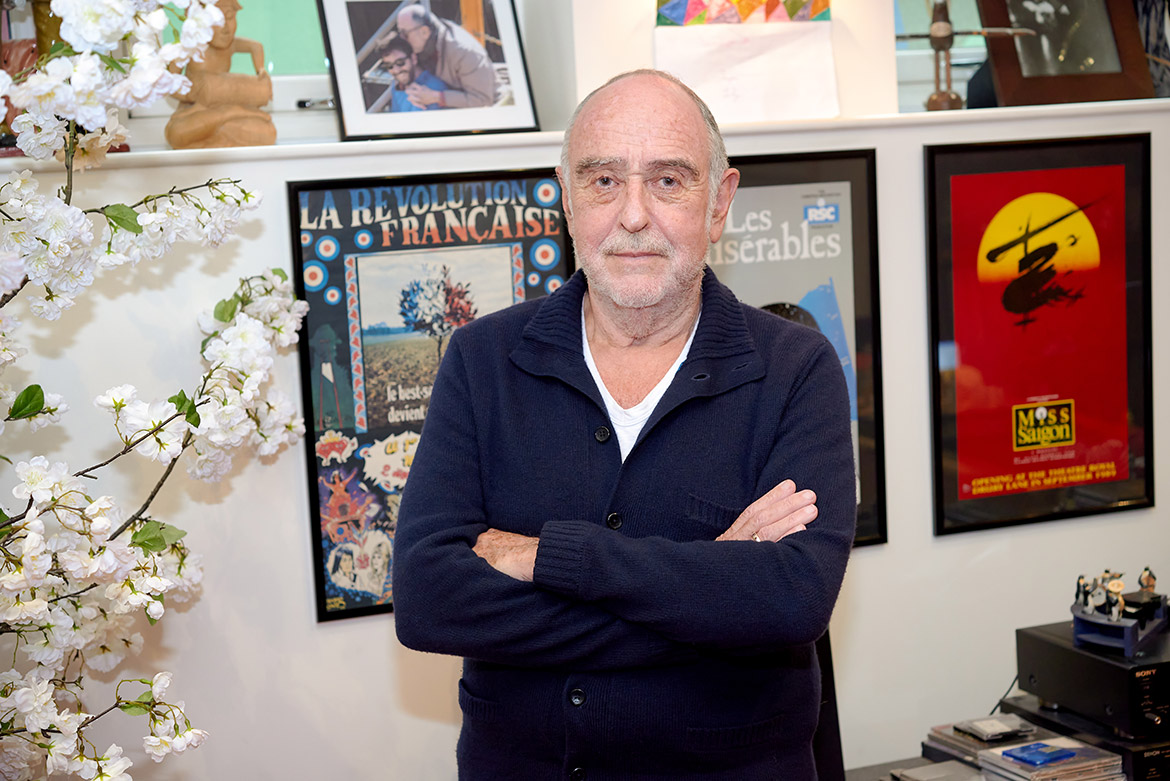

MUSIC AS A RAISON D’ÊTRE

When the world-renowned composer welcomes us to his Chelsea home, his frustration is palpable. We meet during a phase of respite between two lockdowns, but theatres remain closed and he admits to being as restless as a caged tiger. “If I’d have felt tired or if success had started to fade, now would be a good time to call it a day. But last year was one of the best years I’ve ever had!” At 76, Claude-Michel Schönberg still has new shows to bring to the stage, and productions to oversee on all continents. He is an accomplished and revered artist, so it is intriguing to find out exactly what it is that still keeps him going. He wrote a song which has sold over one million copies.

He composed Les Misérables – the longest-running musical in the West End (the second longest worldwide), which critics have often cited as one of the greatest musicals ever made. His shows have been produced on Broadway and on hundreds of stages over the world. He has received a Golden Globe, been nominated for an Oscar, and has won every possible accolade in the industry including the Laurence Olivier, Tony and Grammy awards. Millions of people have been moved to tears by his music, and one of his songs has become a protest anthem for oppressed people around the world.

But it is not money, fame, or the desire to leave his mark and change the world that drives Schönberg. In the course of this interview, we discover a man wholly consumed by the need to create music, who confesses that he had little merit in choosing his career, because music is the only way he knows how to live.

Could you tell us about your family background?