![]() Reading Time: 11 minutes

Reading Time: 11 minutes

Writer, author, documentary filmmaker & reporter

After graduating from SciencesCom in 1998, Stéphane Dugast quickly embarked on the adventure of the open sea by becoming a reporter for Cols Bleus, the magazine of the French Navy. Although he is a reporter, director, author and lecturer, we could also describe him as a storytelling explorer.

In a nod to Arthur Rimbaud, one of the many heroes of his youth, we could describe Stéphane Dugast as a ``man with soles of wind``. When we ask him to go back to the sources of this appetite for the unknown, exoticism and the ends of the world, he takes us back to Nantes, between the river Loire and the Sillon de Bretagne, where the young Stéphane first felt the call of distant horizons.

Can you tell us about where you grew up?

I spent my childhood in Saint-Étienne-de-Montluc, on the north bank of the Loire estuary, about twenty kilometres west of Nantes. My grandfather had a mill with an adjoining chapel, on the hills of the Sillon de Bretagne. I grew up in the countryside, in the marshes that lead down to the river Loire. With my brother and cousins, we went frog gigging and raced around on our bikes. It was a wonderful playground and we built huts, rafts and boats from bits and bobs. The boats sunk more often than not. In short, in reference to Jean Becker’s film, it was a childhood in the marshes. I was very interested in imaginary worlds, the cinema of Eddy Mitchell and the Dernière Séance, with his war films and westerns, and all those films that told of elsewhere.

The landscapes of my childhood were rural and earthy, with the promise of the unseen ocean nearby. If I had to remember only one image from that childhood, it would be of the big oak tree where we built our wooden hut adjoining the vineyards and my grandfather Jean Redor’s ancient stone mill. Our imagination always ran wild. As Chouans or confederates, we defended ourselves from attacks by republicans or Indians. We were dreamers and pioneers but I always wanted to go and see what was behind the horizon.

All children have dreams about their adult lives; what were yours?

I never talked about my childhood dreams because I was scared of being told that reality was just around the corner. My first dreams of open spaces came to me while I was growing up between the river Loire and the Sillon. The promise of elsewhere was calling. As a teenager, I felt good about myself but began to long to go overseas, to the desert, the tropics, the ice floes and all those other places that you dream about when you’re sitting at home. Each time I saw a boat, I wanted to go aboard and cross the ocean to the end of the world. I watched the Indiana Jones films so many times I’ve lost count and of course I dreamed of becoming an archaeologist.

I had the complete collection of Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, so of course I dreamt of coconut palms, desert islands and all the things that make up the explorer’s “playground”. And what had to happen happened: I ended up dreaming of becoming an explorer.

What kind of a child were you?

I was sociable but a bit of a loner. I was never afraid of being on my own but also able to fit in with a group. After all, I was a reporter on board navy ships for sixteen years, so you had to have some social skills to fit into that environment.

I was curious and attracted to everything; after meeting a baker, I wanted to be a baker, after meeting a writer, I wanted to be a writer… However, I soon realised that storytelling was my thing. I started a newspaper at school, where I wrote my first column about the film Crocodile Dundee. I got a taste for writing. I mistook myself for Arthur Rimbaud and wrote poems to my girlfriends until getting 4/20 in French for my baccalaureate brought me back down to earth a bit…

That didn’t stop you from writing books later on! We’ll come back to that. In the meantime, what did you study?

I took my baccalaureate in 1992, at a time when everything was possible in Europe. The USSR had disbanded and I was learning Russian and dreaming of working in Eastern Europe. I ended up studying economics in Nantes, just across the road from Audencia! In my heart, I still wanted to travel but my dreams of exploration and writing were fading. I put my energy into sport and competed in triathlons.

After my bachelor in economics, I headed to Lille to do my master and spent an Erasmus year in Ireland. I became a columnist at the France Bleu Nord radio station and that was the trigger! Telling stories to others was what I wanted to do. Back in Nantes, my mother told me about a postgraduate course at SciencesCom. I saw that an alum, Alexandre Boyon, had become a sports journalist at France Television so I called him and he advised me to join, telling me it would open the doors to becoming a journalist. I think that’s what motivated me….

My years at SciencesCom were both instructive and festive. I had a great time but the last six months were tough as I spent a lot of time at my mother’s bedside in hospital. She died at the end of the year. After SciencesCom, I wanted to ‘eat’ the world but I had to do my military service first. Luckily, I got into ‘Sirpa’, the army’s information and public relations service.

And your military service gave you the opportunity…

At the end of my television internship at Paris Première, I moved to the editorial staff of Cols Bleus, the magazine of the French Navy. I ended my military service as an able seaman and tried to get a permanent job at Cols Bleus. My editor gave me 48 hours to prove to him that I was the right person for him to hire. I came back with an interview of Robert Hossein who was putting on his show “Celui qui a dit non” about General de Gaulle, hardly suspecting that the majority of the navy had not been very pro de Gaulle! By chance, my superior officer was a Gaullist; he hired me and that lasted 16 years.

For a long time, I was the only reporter at Cols Bleus. I was finally able to travel, fulfil my dreams, make documentaries… The last years at Cols Bleus were nevertheless difficult. I was put in a siding and didn’t travel anymore. This gave me the time to write a biography of Paul-Émile Victor, take a course in geopolitics at IRIS (Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques) and a course in creative writing before finally being promoted to editor-in-chief of the newspaper!

What do you think was your first real exploration?

It was in 2001. My coverage of the Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier had gone badly; I was on the verge of quitting the Navy when I was given the chance to join a ship on its way to Clipperton, an isolated French atoll in the North East Pacific. I managed to get aboard ship as it passed through the Panama Canal. When we approached Clipperton, I found myself facing the mysterious island I had dreamed of and fantasised about in my reading. Nevertheless, frustrations bubbled to the surface as the boat only stayed there for three days, enough time for the army to restore the marks of French sovereignty and to make an inventory of the crabs, birds and coconut trees. I counted them myself; there were exactly 387 at the time!

Three days is not very long, I wanted to stay there for two months! However, this first report enabled me to scout for my second trip to Clipperton, which led to my first documentary for Thalassa, a legendary TV programme that I filmed in 2003 with the renowned polar explorer Jean-Louis Etienne as my main character. In 2015, I returned to Clipperton, with an international expedition and was how the atoll had changed. Rats had replaced the crabs and the beaches looked very different due to erosion and rising sea levels…. Proof that Clipperton is a French sentinel in the middle of the ocean.

To come back to solitude, is it an inevitable part of being an explorer?

Yes, partly. I dream of being Robinson Crusoe alone on a deserted island like Clipperton. Solitude means you have to face yourself, with your qualities and faults. When I cycled through France for my project La France Réenchantée, I had long moments of solitude, but if you’re not afraid to embrace it, solitude can make you feel alive and put you in touch with the precious things in life. Similarly, I have sometimes found myself alone in corners of the Arctic. The relationship with nature is very powerful, both majestic and terrifying. From a very reassuring blue sky, all of a sudden, the wind starts to blow, you are cold, you can’t take shelter, the ice is thin and threatens to give way under your weight… You find yourself face to face with yourself, which makes you both fragile and strong. The link between life and death becomes tangible, immediate, reminding us of that very fine line that we so easily forget in today’s consumer society.

People say you are an explorer; do you accept the description?

I don’t know if I can call myself an explorer. My daughter Joséphine always tells me that she doesn’t know what to put in the boxes when asked about my profession. Author, writer, director, explorer? In my opinion, many explorers are real scientists, archaeologists, oceanographers… Others are more sporting or heroic, like Mike Horn. As far as I am concerned, I explore to share stories and transmission is important to me; my parents were teachers… I like to turn on the light and say that everything is possible. So I am also a transmitter, a storyteller, who makes films, documentaries, books… I also work for the press, Historia, Terre Sauvage, Figaro magazine, Géo and Détours en France.

When I was asked to join the Society of Explorers, of which I have been Secretary General since 2015, I hesitated for a long time. For me, explorers are Paul-Émile Victor, Théodore Monod… I accepted because the question remains open. We have real debates about the differences between an explorer, an adventurer and a traveller… I am a traveller when I go to Venice with my wife for the weekend. An adventurer takes risks and expects the unexpected. Explorers are not necessarily carrying out something useful, instead making a beautiful promise made to society. Uselessness takes on its full meaning when it is shared, hence my need to tell and transmit.

Who has inspired your calling for exploring?

There are so many! Paul-Émile Victor of course, especially as I’m his biographer. Then there’s Jean-Baptiste Charcot, scientist, medical doctor and polar scientist, himself a mentor to Paul-Émile Victor. The fascinating Philippe de Dieuleveult, who inspired a whole generation with his TV programme La Chasse au Trésor (The Treasure Hunt) in the 1980s, who disappeared in the Zambezi Falls and whom we later learnt was an agent of the DGSE (French intelligence service)… The writer and novelist Joseph Kessel, of course, whose books I devoured. There are also the fictional figures, like Indiana Jones, who shaped my desire and need for adventure.

You pay particular attention to the world and the people who inhabit it. Are you empathetic?

When I first started out, I travelled a lot to soak up exotic and unexpected experiences, but I soon needed something else. I wanted to understand the planet and the people who live on it; perhaps this is empathy. In any case, I try to give some of my time and energy to humanitarian causes. I’ve been quite involved in the NGO Aviation Sans Frontières and have written a book for them. I have been on the ground with them and have accompanied sick children to Burundi…

I also try to get involved in these causes through the Explorers’ Society. We will soon be hosting a director who has followed a migrant artist on his journey across the Mediterranean. There will be volunteers from SOS Méditerranée who will tell their stories of the people who are ready to take any risk to cross the sea. It is another form of exploration, so much more risky than the one I, as a westerner, accomplish.

The shelves in your office are groaning with books. Can you share some of the titles with us?

Just behind me is a shelf of graphic novels; I’m crazy about comics, especially adventure comics. If I had to choose just one, it would be R97, les hommes à terre by Bernard Giraudeau and my friend Christian Cailleaux. It tells the story of the sailors on board the Jeanne d’Arc, the French Navy’s ship. I also have many reference books on exploration. I would mention Michel le Bris, the creator of the Étonnants Voyageurs festival, and his Dictionnaire amoureux des explorateurs, and then of course L’Usage du monde by the Swiss travel writer Nicolas Bouvier. At the top, there is the complete collection of Joseph Kessel’s works, alongside works by Alexandra David-Neel, Robert Capa and many others. There is a pile of novels waiting to be read, and, dare I say, a shelf with the fifteen or so books I have written myself.

Can you tell us about your next adventures?

I’m a bit superstitious about this; I don’t like to talk about projects that I haven’t signed up for yet. However, I am definitely going to be travelling through the canals of Patagonia and along the Antarctic Peninsula as a guest speaker of a tour operator. I would also like to start writing screenplays, fiction for comics and, ultimately, for film. The Société des Gens de Lettres has just accepted me on a course I have been yearning to do for a long time. I have written about fifteen books, atlases, illustrated books, surveys, a biography…. and I have the impression that in terms of publishing I have more or less done the rounds. I think it’s time to move on to stories that are a little more universal, and even some fiction.

What advice would you give to Audencia students who want to follow in your footsteps?

First of all, I would advise them not to set limits for themselves. I would tell them that everything is possible, that utopia is a nice word. To quote Theodor Monod “Utopia is not the unattainable but the unrealised”. I think I’ve taken the utopian route. I believe that if you have a dream you can go for it as long as you try to align what you have in your head – this intellect with which you make your dreams – with two things: your own eyes, which are not yet very sharp when you leave your studies, and your heart and guts.

However, you should never lose sight of the fact that being an explorer looks great on paper but is very vague in terms of a career and not very lucrative! Personally, I accept this freedom, which means that some months you struggle to make ends meet while others are more comfortable. It’s part of the deal and you have to know that before you start. At the beginning of my career, Jean-Louis Etienne said to me: “You’ll see, if you want to do this job, the main thing is to last the journey”. In other words, you can make a few hits, do some great exploring followed by a beautiful book; it’s hard not to get carried away, but it can all stop as quickly as it started.

What did you do last weekend? And what will you be doing next weekend?

On Saturday I worked, because you can’t always count the hours needed to get a job done. In the evening, I watched Black Hearts, with my family, a series about the Special Forces in Iraq. On Sunday, I went for a three-hour ride on a gravel bike in the Bois de Boulogne – I need nature and chlorophyll. My wife and I are also planning to go to the cinema and see an exhibition. If you’re going to live in Paris, you might as well let yourself enjoy life in the capital, which has so many treasures.

Is it difficult to reconcile your passion for exploring with family life?

My daughter Josephine is 14 and I was 35 when she was born. I’ve always tried to give her quality time over quantity time and favour projects that might take me a month to complete, but that will result in a book or a film. Moreover, as an explorer, you are often behind a computer building projects and coordinating them. Even if I do travel a lot to festivals in France, I am still at home a lot. In the end, I’m away two or three months a year, and not all at once, so yes, I manage to reconcile my explorer’s life with my family life.

![]() Reading Time: 10 minutes

Reading Time: 10 minutes

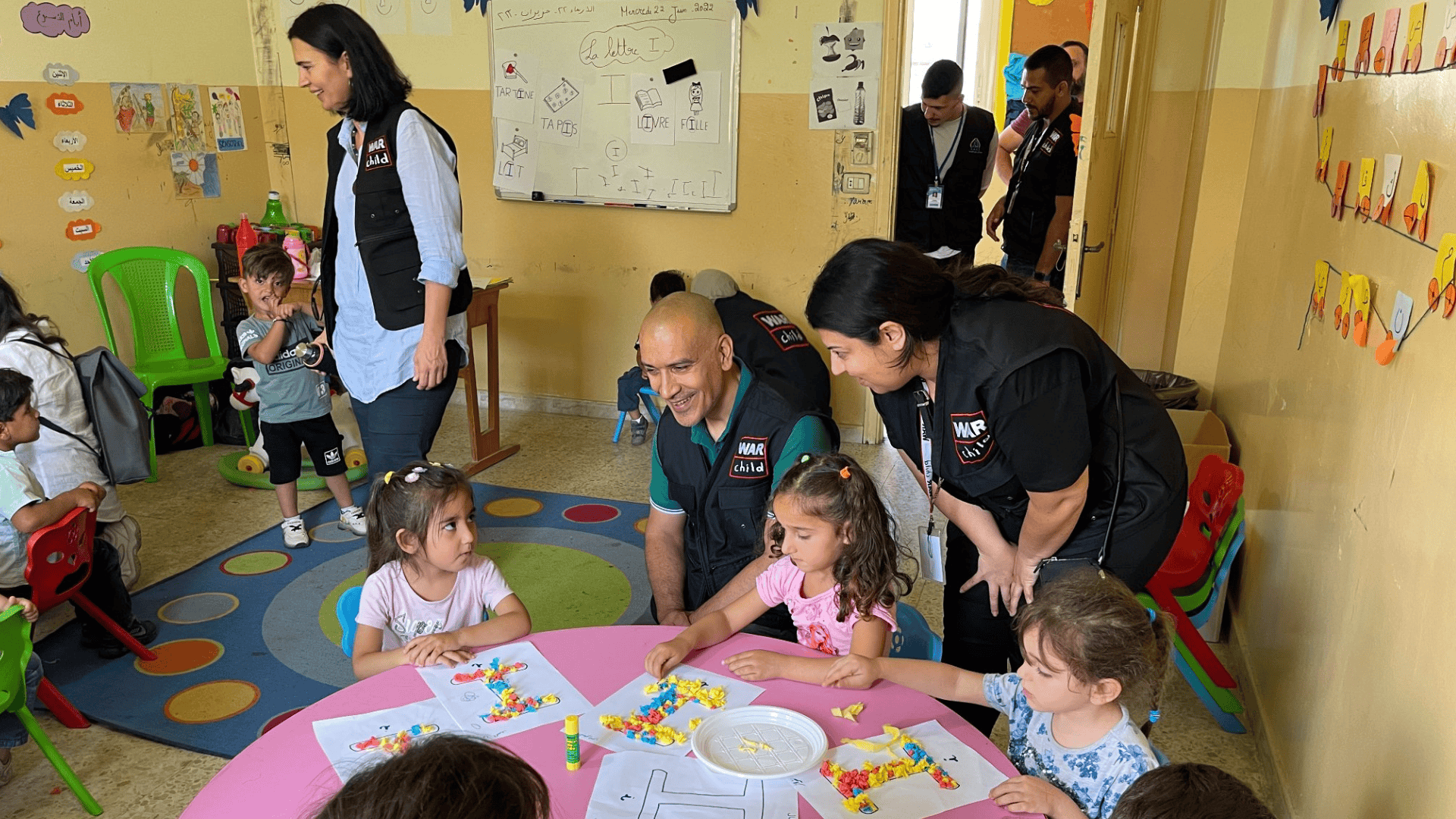

CEO War Child

In 2021, Ramin Shahzamani was appointed CEO of War Child, an Amsterdam-based NGO that supports children affected by conflict around the world. Ramin, who has spent most of his career in the humanitarian sector, brings with him years of experience in international cooperation and fieldwork. He has been on the front line in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Afghanistan, Colombia, Peru and Zambia.

In this brief presentation of Ramin Shahzamani, we mention no less than eleven countries. How else to describe the incredible international journey of a man whose career is driven by the desire to help the most disadvantaged?

Although he is realistic about the scale of the task - some 220 million children are affected by conflict around the world - Ramin is nonetheless fundamentally optimistic, an essential trait for working in the humanitarian sector.

You were born in 1970 in Iran; can you tell us about your childhood there?

The first eight years of my childhood in Iran were very normal and happy. I was a playful child sometimes getting into trouble but certainly enjoying life with my parents, brother and sister. My father was head of accounting and finance for Iran Oil, and my mother worked at home taking care of us.

From 1978, things started to change with the Iranian revolution. At first, it was quite fun because we didn’t always go to school and kids always like that! Then it became a bit more complicated because it was not a totally peaceful revolution. Our parents tried to protect us as much as possible and they did the best they could in a context where the changes soon had a radical impact on our lives.

How did you deal with leaving Iran at the age of 10?

Iran Oil’s offices were closed during the revolution. In 1979, the company asked my father to go to the UK to reopen the London office and we joined him there a year later. Then things got complicated for my family, and, without being too cryptic, my parents decided not to return to Iran but to head for Canada. I was eleven years old.

Arriving in London was tough as neither my brother nor I spoke English. We had to learn the language and adapt to a new culture in a difficult context: Iranian immigrants were stigmatised because of the Islamic revolution and the American hostage crisis. At the age of 11, you can already feel the discrimination. Children can be quite mean to each other and sometimes adults as well.

These events and major changes in a child’s life can shape their character, for better or for worse. Those years were important to me and certainly played a role in the decisions I made later on, giving me the desire to do something for the improvement of society.

What were the first years in Canada like and when did you consider that you had become Canadian?

For my parents at least, there was a lot of pressure. My father had a very good job at Iran Oil, and after he left, our lifestyle became more modest. Technically, we were not refugees, we had immigrant status, but in reality, the difficulties were much the same. However, my parents always placed an emphasis on education as the path to personal and professional success. As an immigrant, there was always a sense of having an additional obligation to succeed.

To be honest, the first three or four years in Canada were complicated, but things became easier once I mastered the language skills. I became more confident, developed friendships and started to feel like I belonged. Canada is a fascinating country for this. I always say I’m Iranian-Canadian and the beauty of it is that nobody questions it. I’m as Canadian there as anyone else and everyone considers me as such.

What kind of student were you, and what were your first jobs?

I think I was a pretty good student, but not outstanding. Like many teenagers, I struggled to find the link between subjects I enjoyed and what I wanted to do later. I really liked biology and microbiology, and later computer science, all of which were useful for my general knowledge but not directly for my choice of career.

After my first degree, I started an irrigation business with a friend I met at university. It was quite successful, but I realised that I needed other kinds of stimulation than the company was able to provide. My job lacked meaning and I struggled with this for several years before returning to university to get a degree in computer science. When I graduated, I could have gone to work in the private sector, but I had the opportunity to join a local NGO in India, as part of a Canadian government cooperation programme. That placement was my first experience of working outside Canada and it made me realise that social justice issues were at the top of my professional agenda.

So your time in India revealed your desire to be involved in the humanitarian sector

Absolutely. In fact, I have always been concerned with social justice and issues of peace and war in general. However, it was in India that I was first able to work in a structured way on social justice issues from a civil society perspective. After that, I applied for a job with the World Federalist Movement-Institute for Global Policy (WFM-IGP), a New York NGO. WFM-IGP is committed to the realisation of global peace and justice through the development of democratic institutions and the application of international law. I started out using technology for the communication purposes of the organization before getting involved in programmes, which clearly reinforced my calling to work in the humanitarian field.

I moved to the D.R. Congo to be the Country Director of the NGO War Child and my work shifted from human rights to humanitarian and development work, but of course, they are closely related. War Child’s mission is to provide support to children affected by conflict. In the D.R. Congo, I remained in the field of human rights, children’s rights to be more exact with practical programmes. For me, it was a great opportunity to work on projects that were making a real difference to people’s lives.

You have managed local War Child branches around the world. To what extent did you see suffering and how did you deal with it?

Suffering was certainly omnipresent and I saw it directly because I was living there. However, going sometimes without electricity or not having access to clean water are comparatively small hardships. You do observe true suffering and feel close to it but are not experiencing it directly. We are in these countries as foreigners and we work for organisations that have certain safety standards and take care of their teams. However, it is not unusual to be confronted with difficult security situations. I have been in some. In some countries, you are somehow close to the fighting that breaks out. You hear it and sometimes you see it. When I was in Afghanistan, the country was volatile and unstable. Some of our friends were killed. There were a lot of precautions to take. So you try to have mechanisms to deal with the pressure and the stress. For some people it’s doing sports for example. In D.R. Congo we could go swimming in the lake which was probably as safe a place as anywhere. That was not the case in Afghanistan, but we could still take a week off every now and then to get together with colleagues outside the country, to rest before coming back to our work. This was not the case for our local colleagues.

You changed countries several times. Is international mobility inherent to the humanitarian sector?

I spent almost three years in the D.R.Congo, two in Afghanistan and four in Colombia with War Child, then five years in Peru and two in Zambia for the NGO, Plan International before becoming CEO of War Child at the organisation’s headquarters in Amsterdam. It is common practice in the humanitarian sector to change countries often, at least for people who have careers in the field and who need to be close to the support programmes.

Contracts generally last between two and five years depending on the organisation and the security conditions of the country. This allows individuals to gain both personal and professional experience. The rotations allow organisations to bring in new ways of thinking and approaches to the field.

When you are in the field, you usually hear about upcoming opportunities before your contract ends. You can then express your interest to the NGO’s management, who will decide whether you are the right candidate when a new position and destination become available. Career development is based on opportunities and the match with your skills.

What made you decide to enrol in the EuroMBA programme?

Even though non-governmental organisations are not based on profit, their set-up is very similar to any other business. You have to generate income and develop products and services. You build teams, have a strategy and all the departments that any other company has. At War Child, we have a marketing department, for example. I’ve always thought it important to bring a business mentality and approach to the places I have worked. Doing an MBA helped me gain useful business skills. Most of the courses on the EuroMBA programme were taught remotely but we also spent a residential week in each of the participating schools of the consortium, including Audencia. I was in Afghanistan then and it was very intense, but I was able to devote time to coursework because it wasn’t like I had much of a social life there! Due to time and life constraints, I was late in handing in my dissertation, but I graduated – finally – in 2022.

What does your position as CEO of War Child mean in practice? What are your priorities?

We have been working on two major transformational and strategic changes for War Child. The first is to our structure where our guiding principle is to transform into becoming a network expert organisation. We want to move from a European-based organisation to a global, decentralised organisation where power will be shared between the different locations where we operate. Decentralising expertise, so to speak. This means giving more decision-making power to the local offices where the impact of our work is strongest. This transformation reflects an underlying trend in the humanitarian sector, where issues of equity and equality are prominent.

The second is to scale up our work and reach more children that need our services. War Child has developed real expertise in certain areas such as education, mental health, psychosocial support and the protection of children affected by conflict. Currently, our programmes have an impact on around 300,000 children per year, but according to the latest UN statistics, around 220 million children worldwide are affected by conflict. There is a big disparity between our impact and actual needs. To undergo this transformation, we need to develop more scientific, rigorous methodologies, not only to implement them in our own programmes but also to make them available to other organisations.

My main job as CEO is to drive the levers that will make these strategic priorities a reality. I have a great team pushing in the same direction and moving forward. Of course, we have to be realistic about the huge challenges we face because of the suffering of so many people in the world, but that doesn’t stop us from being optimistic that we can make an impact with War Child. My team and I are convinced of this.

How has War Child been able to respond to the needs of children in Ukraine?

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, more than 7 million children have had their lives – including their education – irreversibly disrupted. Displaced from their schools, homes and, in many cases, their country, children are experiencing unthinkable compounded learning loss; first from the COVID-19 pandemic and now from war.

In May 2022, the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine (MESU) and the largest education non-profit in Ukraine, Osvitoria, approached War Child Holland to find a solution to reach and teach mathematics and reading to some of their youngest learners – children in grades 1-4.

War Child Holland took on this challenge and began the process of rapidly adapting its already proven Education-in-Emergencies programme, Can’t Wait to Learn, to meet these new demands for greater scale. This required a re-programming of the app to make it available – for the first time – on personal IOS and Android devices, along with its standard practice of co-creation and curriculum alignment with the government. Each version of the app is also uniquely designed with local children, educators and artists to reflect the culture, language and look of the country to make the learning experience for children feel familiar as well as fun.

In addition we are working with local partners to provide mental health and psychosocial support in protected spaces for children. These methodologies have also been scientifically proven to reach positive outcome for children.

What are you most proud of at War Child?

I’m really proud of the direction we’ve taken at War Child and the fact that we’ve put two big transformational changes on track. Of course, we’re still a long way off, and I’ll be even prouder when we’ve achieved those two goals. After all, we could have just carried on working the way we already do, but instead, we’re taking a pretty bold path to challenge ourselves and make these transformations: sharing our power and looking at what it really takes to expand our impact and reach millions of children.

Do you have children of your own?

I have a stepdaughter who is 22 now. She was with us in Colombia and Peru before heading to France to become a pastry chef.

What and where would you like to be in ten years?

I must admit that I don’t look that far ahead. Professionally, my goal is to complete my task as CEO of War Child.

What are you going to do with your weekend?

This weekend is my partner’s birthday. One of the things we’re planning is to go and see an art exhibition that’s on in Amsterdam at the moment.

I read that music is important in your life. Can you tell us what it does for you?

Music does play a big role in my life. Of course, I have my preferences, but I like all kinds of music. Each one touches me in some way. It can be a rhythm I like or certain lyrics I can relate to. Music is also very important for War Child, which is supported by many musicians and has been built using creative methodologies to support children’s mental health and psychosocial wellbeing. Therefore, I have a personal connection and a kind of organisational connection to music. I listen to everything. This morning, for example, I listened to Lennon Stella.

![]() Reading Time: 11 minutes

Reading Time: 11 minutes

Founder & CEO Webhelp

“I was certainly lucky to grow up in a healthy business environment and to have received an education that favoured due diligence. It is obvious to me that a company must be profitable to survive and grow. You need a simple business model where you understand what you are selling, know what it costs and can anticipate what you will make.

In the early 2000s, however, these principles were not in vogue. The era of the new economy favoured originality over profitability and we were talking about disruption, first mover advantage, winner takes all”, writes Olivier Duha in his book “Think Human – La révolution de l’expérience client à l’heure du digital” published by Eyrolles.

Twenty years later, the CEO and founder of Webhelp (120,000 employees in more than sixty countries) can look back on his company’s flawless track record, which quickly combined disruption and profitability to become one of the world's leading providers of customer experience and relationship services and solutions. “If there’s a message that I would like to pass on to future entrepreneurs, it would be to say that there are endless opportunities out there,” Olivier says, choosing to sum up his thoughts with the adage: The sky is the limit.

I was born in Dax, in the Landes area of southwestern France, a fairly poor, agricultural region where people like to live, party and play rugby. My childhood was good. My father was a self-taught retailer and I probably inherited the entrepreneurial values he shared with us at home. I was a very active child, turning my hand to many things and playing lots of sport.

I only became interested in studying when I got to secondary school and realised that learning and knowledge could be useful. Economics was my favourite subject. I think the first books my mother bought me were about economics; I remember reading Robert H. Waterman’s bestseller, The Price of Excellence, as soon as it came out. My good results in economics and maths naturally led me to business schools.

So you joined Audencia?

Not immediately. After glandular fever kept me in bed for a good part of my preparatory years in Pau, I got into Sup de Co Poitiers (now Excelia, editor’s note). In 1992, I went on to Audencia to follow a Master’s degree in Management Consulting Engineering. I have always been interested in the analytical and strategic dimensions of the business world and the Audencia degree, very much focused on the engineering consulting profession, suited me perfectly. It was an exciting year, which led to an internship at L.E.K Consulting.

On the subject of internships, I remember one of my classmates wasn’t sure which direction his career should be taking so hadn’t secured an internship. I had a second internship offer in HR consulting from Hay Management, which I turned down but managed to convince them to take my friend instead! At the time, he didn’t find the opportunity particularly motivating but 30 years later, after an entire career in HR, he is a successful HR Director.

How did your first professional experience leave its mark on you?

I joined L.E.K Consulting at the same time as two other trainees from HEC and Centrale. The head of L.E.K. got me worried by telling me that there would be only one job up for grabs at the end of our internships, and that my Audencia degree would probably not be a match for the ones from HEC and Centrale! In short, I was challenged from the start, and I realised that adversity suited me, that it made me want to surpass myself. In the end, I was the one who got hired!

And this story repeated itself quite quickly. L.E.K is an English firm and after a six-month stay in the London office, I returned to the Paris office and applied for a position in Sydney. Again, I was told that I was not at the top of the list and again, I got Sydney! It was the second small victory in my young career. I stayed in Australia for one year and it was an important chapter in a career that I wanted to be as international as possible.

What do you think your bosses saw in you that made the difference?

I think I had a higher capacity for work than my colleagues did and I certainly remember working a lot. I also think I am extremely reliable, serious and methodical. Then again, I am just repeating what I was told at the time! I am a hard worker and I have a real work ethic. I’m not necessarily the smartest, but I think I was appreciated for this combination of discipline, conscientiousness and enjoyment of work. You can only work hard if you enjoy it! I was perhaps a little more passionate than the others were. It was all these things that made me more quickly spotted by managers, consultants and partners.

Why did you decide to return to the classroom to pursue an MBA?

I loved working in consulting. The positioning of L.E.K Consulting was very analytical. It was a lot of thinking about beautiful strategy cases. Intellectually, I found it fascinating but I had been there for five years and had reached a stage where, in order to move my career forwards, it was essential to do an MBA. In 1997, I applied to and was accepted at INSEAD. To be honest, at the outset, I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about becoming a student again, it was just a means to an end. However, once I was there, I had an amazing year and I often tell my children how great it was to be able to return to school at the age of 30. First, because you have a much higher level of maturity. Secondly, because you can relate and refer to your business experience. Nothing is conceptual anymore, nothing is theoretical and everything connects much more easily with reality. There were 47 nationalities in my class making for an intense and intellectually rich experience.

What did you do after your MBA?

I went back to consulting because I felt good there. I loved L.E.K. and fully intended to return to them but I had the opportunity to join Bain & Company, a larger American firm. Returning to professional life came with a heavy workload. It was the end of the 1990s when the Internet was taking off and you could feel that a new world order was about to emerge. Even though I loved what I was doing at Bain & Company, I felt the urge to become an entrepreneur. I just had to find the right idea. During that time, I recruited Frédéric Jousset to strengthen the team for the last case I managed. However, he wasn’t really suited to consultancy. Instead, he had a very entrepreneurial profile, so I suggested that we set up a company together, which would become Webhelp. We remained partners for many years but he has since taken a different path and I am now on my own at the helm.

Can you take us through the inception of Webhelp?

The company started on a whim. Afterwards, there are things that seem obvious, but at the time, it was more a question of intuition. It’s not entirely rational, you just feel that a combination of factors is there and you have to seize it. There is also a bit of luck, but as Pasteur said, “Chance favours only the prepared mind”, and I think I was prepared.

We realised that the Internet was turning into a huge library, so it needed a librarian. At a time when Google didn’t yet exist, the idea was to build a human-assisted search engine. We wanted to disrupt the world of the call centre by imagining a much more digitalised customer relationship, through interfaces such as emails, chats, videos, etc.

This idea was very successful and we quickly attracted big investors like Bernard Arnaud, via Europ@web, our first reference shareholder. We created a buzz and the product quickly gained notoriety but, it wasn’t profitable! At the time, monetisation through advertising and data worked well in theory but was very different in reality. Each time someone asked a question on the platform, we lost money, which meant I knew how many days were left before I had to rewrite my CV!

We remedied this by moving from B2C to B2B. We quickly won our first clients who were Internet service providers and the first e-commerce sites. We recruited ex-consultants from consulting firms to strengthen our upstream consulting, we came up with a very techy, innovative offer and we decided to relocate resources to reduce costs. All these decisions explain the early success of Webhelp, which then established itself in France as the new player in customer relations outsourcing.

If you had to share one piece of advice that you learned from your entrepreneurial adventure, what would it be?

I think we all too often underestimate a company’s potential for development. If I had a message to pass on to future entrepreneurs, it would be to look out for a world of opportunities and possibilities. The expression “the sky’s the limit” is true and even when you reach your goal, there’s always more territory to explore.

When we launched Webhelp, we set ourselves the goal of becoming the leader in France. This seemed like a far away objective for such a small company, but we succeeded. France represents 4.5% of the world’s GDP, which means that 95% of the wealth is elsewhere, so our next objective was to become number one in Europe. From where we stood, it seemed almost impossible to achieve but we did. So now, when I tell my teams that today’s objective is to be world number one, they think I’m crazy but I always tell them: “If you don’t laugh when I tell you about my objectives, then they are not ambitious enough!”

At the end of the day, the mountain always seems smaller once you’re at the top. This is something I have learned over the past 20 years. As an entrepreneur, it has been a real discovery to realise how much you should not be afraid of thinking big.

However, I have to admit that we have never had any serious failures. Of course there have been ups and downs and difficulties, but no major events that could have endangered the future of Webhelp. This is perhaps partly because we have a very sophisticated risk management system. Inevitably we take risks, because in order to move forward you have to be daring, but the thoroughness of our analysis means that we have never put the company at risk, even in the context of the 27 acquisitions we have made.

Do you attach particular importance to your professional environment?

I have one very strong belief that I repeat to my teams: start with the who not with the what. The women and men who work with us are more important than anything else is. For me, human capital is the combination of an individual’s intrinsic abilities – i.e., their skills on a subject – and their ethos. The right skills won’t work if the right mind set isn’t there.

I spend a lot of time recruiting the right people. I put ethos and mind set at the top of my recruitment criteria. Ethos in a company is like education in a family. You can train people in skills they don’t have, but you can’t change their ethos. Of course, there is no right or wrong ethos, but it doesn’t work to have too many different ones in a company. Diversity is important but it has its limits. A certain cultural homogeneity is necessary to avoid the risk of inertia. So we make sure we have as much diversity as possible in our ranks, while ensuring a certain cultural coherence that tallies with our company. The American professor and consultant Peter Drucker used to say “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”, and it is so true!

Are you prone to stress?

Yes, I am, but I think there are two forms of stress, one that paralyses and one that energises. The latter generates dopamine, and as far as I’m concerned, it increases my energy tenfold. When someone tells me: “With Audencia, compared to HEC and Centrale, you won’t necessarily get a job after your internship”, it stresses me out but motivates me at the same time! I perform better in difficult situations.

In previous interviews, you mention sporting activities. How do you fit sport into your busy routine?

I still manage to do a lot of sport. Rugby and tennis was for when I was younger; now it’s mostly skiing (hors-piste or sometimes extreme) and mountain activities in general (hiking, mountaineering, in winter and in summer)… I also manage to fit in a round of golf when I’m travelling to the four corners of the globe.

Think human, think peace appears on your computer wallpaper. Why did you write this?

Think Human is the Webhelp baseline that goes with our logo because in our industry, human resources are the most valuable asset. In the world of customer relations, the heart of the reactor is the human being.

We assist major brands with their customer interaction issues. We are a consulting firm, an IT firm and a contact centre operator all in one. Therefore, we either position ourselves as a technology company or as a human resources company. I believe that the essential resource is people, not technology. All companies in the sector can acquire the same technology. However, when you manage to retain human resources through the way you treat your employees, you have a competitive advantage that is difficult to copy. Webhelp is recognised for this very people-first approach. In R&D, my investment priorities are training, onboarding, people engagement initiatives, etc.

I also believe that Think Human should be at the heart of brand thinking, for two reasons. On the one hand, the digital effect means the balance of power between brands and consumers has changed in favour of the latter. Secondly, we have moved to an experience economy where we no longer judge just the cost-benefit of a product but also everything that happens before and after the purchase, i.e., the entire customer journey.

I added Think Peace on 24 February 2022, the date Russia invaded the Ukraine…

You took your base line, Think Human, to name your foundation…

We did indeed create the Think Human Foundation with the aim of generating giveback on the subjects of inclusion and education, interesting subjects related to the fact that we are in a very people-intensive business. Initially, it was a fund supported by the company’s founders and shareholders. Now, the idea is to get all employees to participate, even if they only give a few euros. A few euros multiplied by 120,000 people makes for a sizeable annual budget.

What are you most proud of in your career?

Whenever I visit Webhelp sites around the world, I always take the time to have round table discussions with the employees who work in the contact centres. I want to know their take on the company’s culture by asking them the question: “How do you talk about Webhelp to your friends and family? I am very proud of the consistency of their answers, which underline that we make a difference through our social management policy. I am very touched by this. The consistency of our HR policy throughout the company is probably the thing I am most proud of.

Can you take us through a typical day for you?

There are two. The first is when I get to work from home. I can get a lot done by video. In this case, I like to get up early; I start by reading the papers, working and doing 45 minutes of sport. By 9.30am, I’m ready for my first meetings. I work almost seven days a week. I lighten up a bit at the weekend but I still work a bit because I like it.

The second sort of day is when I am travelling. We are present in about sixty countries, with 230 production centres and contact centres. I have to go and see my customers, accompany my teams so I spend more than 200 days a year travelling.

Do you nurture an entrepreneurial spirit in your five children?

It’s important to be influential without being manipulative or coercive. I don’t want to interfere; they have to find their own way and there are no wrong routes to go down. Just because I’m an entrepreneur doesn’t mean they have to do the same! The value of example, which is valid whatever the profession, is the desire to do well, discipline, seriousness, effort. Personally, I try to do everything to the full, and not just on the job.

Your LinkedIn profile mentions that you are a graduate of the Wine and Spirit Education Trust. I guess this means you have a favourite wine!

That’s correct! I am passionate about discovering vineyards all over the world. My favourite wine is Emidio Pépé from the Abruzzo region in Italy… to accompany an autumn meal (with game and mushrooms…).

What are your plans for the weekend?

Some friends are coming to stay with us in Brussels. We’re going to take a little trip to Bruges and Antwerp. A bit of sightseeing, a bit of sport, and a bit of work of course! (laughs)

Where do you see Webhelp five years from now?

Initially we developed the service side where our teams accompany brands throughout the world. We then added an IT department to offer technological solutions in the world of customer experience and then a design solution consulting business for companies that are transforming. I think that the consulting business in particular will become increasingly important. Proportionately, of course, we are getting closer to the world of Accenture on the customer experience side.