![]() Reading Time: 9 minutes

Reading Time: 9 minutes

CEO Schoolab San Francisco

Mathieu Aguesse is a 2015 graduate of ICAM School of engineering and Audencia’s specialised master in Marketing, Design and Creation (MS MDC). From his offices in San Francisco, he runs the US version of Schoolab, an innovation studio that trains, advises and supports its clients in responsible innovation. Mathieu also teaches design fiction and ethical and collaborative innovation at UC Berkeley. ‘Deplastify the Planet’ is one of his flagship programmes.

Mathieu’s story is that of a boy with a passport full of stamps, who, from South Africa to Nigeria, has developed a taste for travel, discovery and relationships, which he carries with him everywhere he goes.

Our conversation takes place across an ocean and several time zones and we pick up the thread of our discussion that started two months earlier.

When asked if he is in San Francisco for the duration, he smiles as if the binary format of the question still puzzles him. For Mathieu, “Staying in the USA or returning to France” is an incongruous choice as the world is full of so many other possibilities too. Mathieu is giving himself time to choose but also time to welcome his third child in the coming days.

Mathieu sees life as a permanent and collaborative learning process in which everything always ends up making sense and aligning when you know how to listen and observe. Discreet and curious, Mathieu doesn't like to talk much about himself: he prefers to talk about his encounters, discoveries and projects. In short, anything that will enhance his perception of the world he lives in with eyes and ears wide open.

Tell us where your wanderlust comes from

I grew up in Africa, between South Africa where I arrived two weeks after my birth and Nigeria. My parents were diplomats, attached to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. They moved around a lot and I guess they passed on to me their thirst for curiosity, discovery and meeting people.

My family returned to France when I was 12 and then, when I was 16, my parents headed abroad again without me. In most families, it’s the children who leave the nest, in mine it’s the other way round. That changes your perspective on life.

So an international career was always on the cards…

Subconsciously, yes.

Between my return from Nigeria and my studies at ICAM and Audencia, I spent ten years in Nantes. Even though I loved my time there, I felt a bit stifled. Deep down, I knew I needed to go further afield.

I have visited about sixty countries in my life, so living outside France was never a case of if but when. I had been ready for a long time when the opportunity arose; I would even say that I’d been waiting for it to happen. Sometimes life creates beautiful coincidences: when I left for San Francisco, my first child was the same age I was when my parents took me to South Africa.

In fact, I would have liked to start Schoolab in South Africa to bring an innovation model to which I’d had access to a country that, in my opinion, represents the future of the world. However, for a company like Schoolab, it made sense to start our international development in Silicon Valley, the most dynamic and powerful entrepreneurial ecosystem in the world. It was a big gamble for us to see if we could exist in San Francisco with our values and differentiation, the ethical side of innovation.

So even though it wasn’t Africa, I seized the opportunity without question and with enthusiasm.

At the beginning, however, your path didn’t look like that of an entrepreneur in Silicon Valley.

I had already sown seeds and they were just waiting to germinate and grow. At ICAM, I had taken part in an entrepreneurship competition around the digitalisation of AMAPs , a very rich experience even if it didn’t go all the way.

However, thanks to the alumni network, after graduating I made a “safe” choice by joining the construction sector, perhaps because I had not yet become aware of my true needs and values: discovery and ethics. Very quickly, however, this conflict of values blew up in my face: I was uncomfortable with the male-dominated environment where the balance of power was profoundly unequal to the detriment of the artisans, the “small guys”. This did not suit me at all and I wanted out.

I wanted to do something radically different and headed to the luxury sector, where, on the contrary, artisanship is a highly valued cornerstone of the industry. However, it’s a difficult environment to get into and no-one wanted to hire me. The result was that, with a partner, I created a start-up for bespoke leather goods.

We had a promising concept, good suppliers and funds raised from the BPI. Unfortunately, like so many start-ups, the ride was not a smooth one. Our project was used as a case study in the HEC Entrepreneurs course and integrating the conclusions proved hugely complicated. Instead of being strengthened, our confidence, in ourselves, our project and each other, was put to the test. What bound us together at the beginning then seemed to divide us, so we decided to stop.

Was abandoning your start-up the hardest choice you ever made?

There’s no doubt that the decision was a tough one at the time, but I also knew that we couldn’t continue as we were and that our chances of success would be compromised if we couldn’t align our visions. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t so much a choice as a necessary step that had to be accepted and digested.

The decision I had to make directly afterwards proved to be more difficult.

What was that?

After ending my start-up adventure, I received a very nice job offer from a fabulous brand of leather goods. It was the kind of offer that I couldn’t refuse and that would allow me to achieve my dream of working in the luxury sector.

I was very excited and happy about the offer, but deep down I had a feeling that I was missing a few strings to my bow, especially in design. This was a thought that had been floating around since creating my start-up and I’d started investigating solutions, including returning to the classroom.

Then I received two acceptance letters on the same day: one from my dream employer and one from the MDC recruitment team at Audencia. I ummed and aahed but chose Audencia. This led to some interesting conversations with my parents who, although they didn’t really get the no-brainer of paying to go back to school instead of accepting a well-paid opportunity, were always supportive.

It was a choice of intuition over reason and I don’t regret it.

So that’s how you joined Audencia?

Yes, for the specialised master in Marketing, Design and Creation, but also for the programme director, Nicolas Minvielle, whom I had met and asked a billion questions about the course, the school, future prospects and more. The role and practices of designers fascinated me.

After my baccalaureate, I had considered studying at the School of Design in Nantes, so I was already gravitating towards that environment: the little seeds I was talking about earlier were planted but I didn’t want to water them too soon, probably for fear of the lack of opportunities but also perhaps because I was too young. At 18, I think I was too young to have been exposed to the realities of life and to be able to make enlightened decisions. I guess my first degree was a precautionary choice, perhaps also by default.

On the other hand, joining the MS MDC programme was a very well thought-out choice, and paying for the course myself, instead of earning a good living elsewhere, gave an extra dimension to the challenge. I knew I had to make the most of the experience.

Looking back, I think that it is very difficult today to do this type of course without a bit of experience under your belt. That’s why I always involve companies in my teaching at Berkeley, so that the students are immediately faced with the realities of systems and organisations. I also believe that my mission as a professor is to accompany students on this path of continuous learning and teaching them how to learn, i.e., giving them the tools to challenge the status quo and think for themselves.

What memories do you have of Audencia?

I’m sure my background has made my memories quite different from those of the rest of the class. Even though I wasn’t yet 30, I’d already experienced entrepreneurship, business and working in the real world.

I think the French education system should value courses like the MDC and Specialised Masters in general. These courses are goldmines that can be an enormous lever for transformation. We should be making so many more bridges between education and work, to allow more people to come back to study at 25, 35 or 45.

When I arrived at Audencia, I quickly realised that entrepreneurs and designers are made of the same stuff! They think with their guts and with their emotions. That’s how you can recognise them: there’s a rather interesting form of collective hysteria in the MDC classroom because the course is creative and gets people moving. The profiles are very (very) hybrid and able to juggle subjects and disciplines. This suited me well because I like the idea of not being confined to a specific box.

Is being unconfined your career secret?

Maybe it is! I think I’ve always regretted my default choices more than the risks I took that didn’t pay off.

Today I see things differently: I accept what life throws at me and then I observe and try to understand the systems in which we evolve and endeavour to remain proactive in order to align these systems with my desires – or the opposite.

For example, in four years in San Francisco, we never bought a car, which is very uncommon here. However, on countless occasions, our friends and acquaintances offered to lend us their cars, vans and even houses. Simply because we didn’t rush into anything, knew how to align our desires with the needs and capacities of our close ecosystem at the right time. The same thing happened to us when we were looking for a house: instead of rushing to make an appointment with a real estate agency, we talked about our search within our circle and went to meet the people we were introduced to. We listened and were open and very quickly found a great place.

It’s the same professionally: you have to be patient and know how to seize opportunities when they arise. To do this, you need two essential qualities: knowing how to conceptualise and express what you do or want, so that you can easily talk about it around you, and knowing how to give back whenever you can, in one form or another.

Is sharing the key to today’s world?

Perhaps more globally, awareness but also permanent transformation. I give this impetus to Schoolab, activating transitions with a rationale of continuous, controlled and flexible, proactive and positive movement.

The people I joined Schoolab with have all left. I stayed. Why did I stay? Because I managed to develop my job and my professional practices, and therefore my impact on the world around me. I regenerated the meaning I gave to my projects throughout my time in the company.

This is what I try to teach my students and the companies I work with. I share my own experiences to help them adopt a positive and sustainable approach to transition. Individuals who start to change will continue changing and, through a form of osmosis, this will continue to have an impact on their activities.

Change is an attitude that feeds on learning, observation and freedom of choice. In order to take power and act on what we want to transform, we must understand the world, not just submit to it. You have to develop critical thinking, which means challenging different points of view. I try to put this into practice in my courses, by inviting pro-plastic lobbyists to my ‘Deplastify the Planet’ programme, for example. We all need to find some depth of thought and reinvest in freedom of choice.

How do you see the future?

That’s a difficult question!

Today, everything is going well professionally. I have just received an award for best teacher at Berkeley. Schoolab is growing, even though we are focusing on slow, organic and qualitative growth rather than scale. By the end of the year there should be ten of us, compared to only two during the COVID-19 period and our programmes are very successful. I have just published an article on Design Fiction in the prestigious Harvard Business Review. However, the future is not just about that. I have two children, and soon three. In ten or even twenty years from now, I want to be able to look them in the eye with pride. Not for my professional success, but for having understood the issues of our time and being part of the solution.

Having children puts things in an interesting time scale and gives depth to my daily action. For me, defining a company’s vision means making sure that the activities to which I devote most of my time contribute to creating a positive impact on the world we will inhabit tomorrow.

I often say, “You can’t go wrong with sustainability.” In fact, you can go wrong, but in the method not the commitment. I am very interested in regenerative agriculture: we are involved in maintaining the community garden and beehive, which I find fascinating. When you look closely at bees, you understand both the way honey is made and the concept of social inequality. You think about healthy eating and climate justice.

When I look back, I have no regrets: I made mistakes, I made choices by default, but I learned. I understood that freedom of choice was the condition for the future, the key to true success, the one that lets you think you are in the right place, at the right time, with the right people and the right impact.

![]() Reading Time: 7 minutes

Reading Time: 7 minutes

Owner & Baker L’Imprimerie

As Emmanuel, he graduated from Audencia’s Grande Ecole Master in Management programme and pursued a career in investment banking. As Gus, he learned to bake at the French Culinary Institute before opening his own bakery, L’Imprimerie, in Brooklyn, New York. If you can’t make it to the Big Apple, check out his Instagram account here: https://www.instagram.com/limprimerie/

L’Imprimerie (The Print Shop) is the name of his bakery nestled in the heart of Bushwick, on the edge of Brooklyn. Gus makes the best pain au chocolat in New York, but he’s not after trophies or fame: Gus has a taste for a job well done. Period!

The class of ’97 may remember a certain Emmanuel Reckel, what happened to him?

He stayed in the City. When you reinvent yourself, sometimes you have to go all the way and slough off your old identity.

What happened on that Monday in September 2008?

That Monday in September 2008? I don’t remember really, it’s become blurred over time. It was a long time ago, but, at the same time, it feels like it was yesterday.

I was the Sales Director of a London-based trading room. I remember going away for the weekend like all my colleagues, and reassuring my clients before I left, telling them that everything would be fine, that there was nothing to worry about. That the management had a plan, of course, and that they would reveal it to us very soon. That we would come back stronger than ever, certainly with a new name.

I think everyone at Lehman Brothers spent that weekend glued to their screens, whether it was the news channels or their Blackberries – yes, we hipsters weren’t yet hooked on iPhones. We were waiting for a message from top management, a reassuring word, a hint of what was to come. Monday arrived and we still didn’t have any news. When we got to the office, they asked us to be gone by noon, taking our personal belongings with but leaving our jobs behind. That was it. Lehman had collapsed.

Is that when you changed jobs?

No. I continued in finance, at Nomura Securities, the Japanese brokerage firm that took over part of Lehman Brothers’ activities in Europe. I stayed in London until I was offered a a two-year expatriate contract as Sales Director in New York.

I went for it and I loved New York. Immediately. I felt like I belonged there. When my contract came to an end and I should have been heading back to London, I didn’t want to leave. I don’t like going back: you rarely find what you’re looking for.

OK, but the route from trader to baker isn’t a direct one…

No.

Well, the first step is still an investment. In my mind, I was thinking of a café, a grocery shop, a place to gather in my neighbourhood. I was looking to buy a building because I didn’t want to be dependent on a volatile real estate market or a landlord who could grant or deny my business its breath of life.

When I discovered this place, a 50-year old printing house with a press that was still in working order, I borrowed the money and went for it. But really, at the beginning it was mainly a café project: I wanted to make bread on the side, rather than buying it from a baker and selling it on.

So what made you decide to become a baker?

It was a personal and professional business strategy as well as the lack of market supply. A combination of all of these, I think.

First, I’ve always been an early riser, so you could say I’m predisposed to baking. However, it was mainly when I realised how good bread was so hard to find in New York that I thought about training and going for it.

I wanted to do the Compagnons du Devoir but I was too old. So I looked at the French Culinary Institute in New York. They have a big programme for pastry and another for cooking. They also have a less well-known bread programme, which is very hands-on and in line with my needs and expectations. Above all, it was intensive: in ten weeks, you learn all about French baking techniques, bread but also viennoiseries and everything that uses leavened dough.

That’s all I use today at L’Imprimerie. We’re very transparent with our customers: we have this very authentic side that ties in well with my French origins, the tastes that I loved when I was a kid and that I share today, so yes, we’re the French Bakery of the neighbourhood and we offer what our customers expect to find in a French bakery.

However, since we’re in New York, we’re free to introduce a few little twists because we have a wide community that goes beyond our French customers. We do chocolate with jalapenos, cinnamon rolls with croissant dough. You could say we have something of a Dolly Parton aesthetic: a bit cheap, but very, very authentic.

Is artisanship in your DNA?

Being a baker is probably more important to me than being French, even if I am what I am. I can handle that and I play on my origins, that’s for sure. Nevertheless, what interests me is to be true and honest and make my business work.

We have a quality approach: each morning, everything is freshly prepared by us and cooked on the spot. I don’t see the point of making a strawberry tart out of season just to make our offer more French. This is not our promise.

I offer a different vision of food in my neighbourhood, this idea of slow food and high quality. But also a presence and a place to live in the heart of the community. I’m neither a co-op nor a neighbourhood association, but during COVID-19, for example, we were there every day and for many people we were a landmark.

Our customers are hipsters, Bobos, guys who work in the City, but also people of more modest means, who work at the hospital just down the street. The idea of quality food should not be the reserve of just a few. I’m trying to develop a business that is sustainable, i.e., economically viable, but that fits in well with its community. I pay my staff on time and my suppliers too. But make no mistake, we work hard, we don’t bunk off.

Being a baker is a tough job in a difficult context

Yes, it’s clearly a difficult job.

During the pandemic, a lot of people started making bread at home. And that’s great because it did them a lot of good, especially for their wellbeing. The kneading itself is quite a meditative experience and then there’s the smell of the dough, the contact, the texture. Frankly, bringing a loaf of bread to life is an incredible sensation.

However, there is a huge difference between fantasising about changing jobs while you’re making your bread at home and actually doing it. The reality of the job is that you have to be there every day, every night, preparing your recipes, shaping your breads, baking them, etc. You carry heavy bags, you stay in the kitchen andit’s hard work. When you are standing all day, you get this feeling of producing, producing, without looking up, even in a craft environment. Some people find it too hard in the end.

Our job is a physical, technical and scientific one because dough is a living material. Depending on the heat, the cold, the hygrometry, it doesn’t react in the same way and you have to adapt.

And of course, being a baker also means being a company director, with all the different hats that you have to wear in today’s world: communicating, selling, managing, recruiting. So yes, you have to keep your feet on the ground. Because I haven’t been a baker all my life, I often feel like an imposter compared to other bakers. However, I think that I may be a little ahead of the game when it comes to managing a business. Having had a previous career has turned out to be very helpful.

You also have a bit of a militant side, don’t you?

No! I’m not here to give lessons to anyone. Not about bread, not about anything. When we launched L’Imprimerie, we could have made a big fuss in the press, made ourselves known in the City, played that card, but I didn’t feel justified going down that route. I’m not one of those bakers who’s been in the business forever, because I didn’t take a specific trade qualification like all the others, and maybe also because today I use my American passport more than my French one.

So yes, there are things that make us happy, like when we were voted best pain au chocolat in New York: we feel that people recognise that we do the job properly. But that’s where it ends. There’s only one thing I want to do and that’s my job, properly!

I want to be at the heart of people’s lives, to create this place where they are happy to come, where they feel good. I want them to recognise us for the quality of what we sell them. Our customers decide what label they put on us.

Do they call us the neighbourhood’s super French bakery or the super queer bakery? That’s fine, just as long as we can see the word “super” in front. I’m not an activist, I’m here to keep my customers coming and coming back, to pay my bills at the end of the month, and to have fun in what I do every day.

What does the future look like for you, Gus?

I don’t know. Who can predict the future?

Is L’Imprimerie doing well? That’s good. We’ll keep working hard, like we have for six years now and taking it one day at a time. I don’t have any plans to expand, if that’s what you mean.

Nor a return to France?

Not back to France, no. I’m at home in New York now.

![]() Reading Time: 8 minutes

Reading Time: 8 minutes

Deputy Director of the MBA Programme, Cambridge Judge Business School

In 2009, Thomas Roulet graduated from Sciences Po and Audencia’s Grande École Master in Management programme. Today he is an Associate Professor at Cambridge University, Deputy Director of the MBA at Judge Business School and co-director of the incubator at King’s College Cambridge. He contributes to numerous magazines and publications, such as Forbes and Harvard Business Review.

He is teased about his accent and his friends ask him to choose the wine at mealtimes. Professor Roulet’s French touch is like a signature that he wears happily, especially on the day after France’s football team defeats England. He even claims to bake his own galette des Rois because “you can’t find any good ones in Cambridge”.

Thomas enjoys this French impertinence, which gives a special touch to his journey from a finance student at Audencia to an associate professor in organisational theory at Cambridge. With enduring ties to France, Thomas delights in a job in England that, in his Harry Potter gown and in 800-year-old buildings, plunges him into the heart of society’s greatest debates on one of the most renowned campuses in the world.

Thomas, tell us about your journey to Cambridge

It’s a long and winding story which started fairly characteristically during my preparatory classes. When I started at Audencia, like lots of others, I thought I would do marketing. In the end, I went into finance and did my year-long internship in investment banking in London.

I enjoyed this first experience but found it disappointing. I wanted to delve deeper and understand what was going on behind the curtain of our social interactions. At the same time, I’d always had this taste for teaching. I imagined what went on behind the scenes, when professors were not in front of their students, preparing classes, correcting assignments, carrying out research, etc. When I came back from London, I returned to the classroom to try and find out more about what was going on behind the scenes.

By then, I’d decided to double up my final year finance course with a Research Master at Sciences Po. In fact, my research internship at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) counted towards both Masters.

I really liked the stimulus of the research Master’s degree, so I started a PhD at HEC. Again, I really enjoyed it. In my second and final year, I was teaching at Sciences Po and Audencia. Once a week, I taught strategy to international students, an experience that I really enjoyed.

When did you decide to export your academic career?

Halfway through my PhD, I had the opportunity of being a Visiting Scholar at Colombia University in New York. I loved it, especially because Audencia had cultivated my taste for the United States.

Then, after my thesis, I needed to choose between Vanderbilt in the United States and Oxford in England, I chose Oxford for its geography, which suited me better from a family point of view at that time in my life.

Oxford was very different to London. The culture there is deeply British and much less international than in London. And the college world is fascinating, with its old buildings that house candlelit dinners and a real English-style academic aristocracy. The codes are very particular. It was then I then decided to pursue an academic career in England rather than in France or elsewhere.

Tell us about the British universities

Academia in France is divided into business schools and technical or generalist grandes écoles, whereas the UK has a real university culture. Business schools are integrated into much larger faculties, with, in my opinion, much more interdisciplinarity.

British universities are divided into departments, like in France, and into colleges, which were originally student residences like the ones you see in films. Today, it is much more than that; everything, including the social life, educational experience, culture and symbolism of an 800-year-old college, takes place there.

For a professor in Britain, taking on responsibility in a college is usual – it is very much about individualised support and tutoring students. Compared to other professorial activities, this part of the job isn’t particularly well paid, but it is highly valued and very interesting.

For my part, I co-direct the incubator at King’s College Cambridge, the former college of John Maynard Keynes and Alan Turing. I really enjoy this aspect of my job, as it is extremely diverse. One of the biggest challenges, by the way, is the funding we get from major donors. Our budget is partly covered by the sponsorship of David Sainsbury’s Gatsby Foundation. This involvement of patrons, particularly alumni, is another marker of difference.

How did your career path take shape between Oxford and Cambridge?

After Oxford, I went to Bath, in Somerset, a medium-sized city with a well-known university. I stayed there for a year before heading for King’s College, the London one – the British like to call places King’s or Queen’s Something. For three years, I ran the Master in International Management there.

In 2018, when the opportunity to join Cambridge arose, I took it and I have since been an Associate Professor of Organisational Theory and Deputy Director of the MBA there. My research work focuses on the sociological and psychological approach to organisations.

You said that you enjoy the backstage work of professors. Can you explain what this consists of?

There’s this idea that professors only work when they’re in a classroom with their students and that the rest of the time they don’t do much. This is not true, of course! I work much harder as a professor here in Cambridge than I did when I was working in finance in London (laughs).

Most of my time is taken up with resarch: collecting data, writing, editing and publishing research papers, supervising PhD students and post-docs. In theory, this represents more than 60% of my time. I also participate in four or five editorial boards of journals where I review papers and do some editing work.

I see research as a basis for engaging in the debates that are shaking up society. For me, research is not about producing concepts in an ivory tower but about asking questions that matter to people and producing ideas that find their way into managerial and societal practice. In the coming years, one of the topics I would very much like to have an impact on is the issue of mental health, from a skills perspective but also with regard to hybrid work, comparing remote and face-to-face.

Teaching is the other main part of my work, which I really enjoy. At Cambridge, we do a lot of tutoring, which gives me the opportunity to teach small groups of three or four students, with a very different relationship to the one you find in a lecture hall.

I teach courses at the faculty of business and the faculty of sociology. Each year I teach leadership and organisational behaviour to over 200 students on my MBA programme. The content is all extremely topical and changes constantly. In the past few years, I have totally adapted my course to the topics of the moment to include themes of hybrid work, silent quitting, Diversity & Inclusion issues, etc. After COVID-19, we rethought the whole teaching structure, keeping some courses online and promoting small agile groups on topical issues such as the Black Lives Matter movement or leadership biases.

Sector bias, gender bias, disability bias, ethnicity bias, etc., contribute to the funnel effect, i.e., the success of a Diversity & Inclusion policy at the bottom of the organisation but its failure at the top. I also do a lot of work on invisible stigma, such as invisible disability or sexual orientation, and how certain categories of people are exhausted by working on raising awareness, the ‘diversity work’ that is asked of them and the risks of burnout and performing badly.

Tell us about your experience at Audencia

It seems like ages ago but sometimes as if it was only yesterday. I think I’ve kept more in touch with the faculty than with my classmates but this is probably due to the career I’ve chosen.

When I wanted to pursue an academic career, I got in touch with a few alumni who had followed a similar route. I was impressed to see that several alumni are quite well known in this field. I am thinking of David Dubois, now Professor of Marketing at INSEAD, who gave me some great advice back then and Fabrice Lumineau, Professor of Strategy in Hong Kong.

As for most people, my student journey itself was a multi-faceted experience. I became who I am now in the classrooms of Audencia, which is undoubtedly why I have kept in touch with quite a few figureheads. I was also president of Réseaudencia Junior, the forerunner of the school’s young alumni association. However, there were also more complicated moments to handle, like losing the student campaign for the BDA (Bureau des Arts). I realise now that at the time it affected my relationship with the school. You don’t always realise how difficult it is for young people just out of preparatory classes to cope with things like that.

If I had to do it all again, I don’t think there’s much I would change. I really enjoyed my AIPM internship year and the international flavour of the school. I felt very French when I started Audencia, before discovering wider horizons during my studies.

My internship year nurtured my desire to live abroad but also to do things to the fullest. This I owe in part to an alum who worked on the desk that recruited me. He was instrumental in giving a chance to a student from the same school as him. The alumni network is one of the assets of this school.

Today, you still have close ties to Audencia

Yes I do; through my teaching activities and as an affiliate professor. At the beginning of my career, I used to come once a week to teach strategy. Now I don’t come as often but as an international affiliate faculty member, I still come over for a few days each year to partner with Audencia professors on their publication process.

More importantly, I’ve been lucky to work closely with some of the faculty, including Sandrine Frémeaux, who was one of my favourite professors when I was a student. She is a wonderful, fascinating person who manages to make law exciting. Today, I have the pleasure of working with her on a paper due to be published soon. It’s a privilege I would never have thought possible back when she was my professor!

How do you see the next stages of your career?

I’m already lucky to be a tenured professor at Cambridge, so I have some control over my choices between research, teaching, student support and influencing public policy. However, the holy grail would of course be to get a professorship.

I am eligible but the application process is long and tedious, as one would expect in such a venerable institution. I filled out a fifty-page application with letters of recommendation and convincing arguments.

However, being a tenured professor gives me the opportunity to do other things besides research, hence my investment in the incubator and in the life of King’s College. I really enjoy this entrepreneurial aspect of my job.

And more generally, how do you see the future?

I live in a country that is going simultaneously through the consequences of Brexit, the pandemic and a global energy and economic crisis. We’ve recently lost a lot of European friends because of Brexit and I’d certainly love to see people return as there are still great opportunities, not just in finance.

I would like alumni to continue to look at Britain as an attractive choice to live and work. For me, expatriation is a great experience, a real asset. I love being French outside France.

We are often caricatured, and in fact, at the university, we French colleagues are seen as the grumblers. In meetings, we’re the ones who argue or get upset and our hierarchy doesn’t always like it. However, I like the idea that in France, we don’t have problems challenging what we think is questionable.

Beyond that, expatriation is an adventure and filled with shared experiences. When I watch football with my brother-in-law, I’m torn between the two sides but I get to win each time! In many ways I feel British today, but for them I am French first and foremost. Maybe it’s my accent (laughs).

My advice to students today is to go for the expatriation adventure, even if it’s just for a few months or even a few years. It’s worth it.

What can we wish you for the coming year Thomas?

A successful application for the professorship, no doubt. Also to have time to spend with my friends, here and in France, and with my parents too.

I don’t have much downtime. I manage to fit in a morning bike ride. I don’t have any wild wishes for 2023, maybe just to feel that the link with Europe is not broken forever.

![]() Reading Time: 9 minutes

Reading Time: 9 minutes

Founder & CEO Solinum

Victoria Mandefield is a social entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Solinum, creator of Soliguide, a survival guide and support for the homeless. She is gaining recognition in France as a key contributor in raising awareness and providing solutions for the homeless. She continues to shake up the world of societal impact, working closely with France’s major support systems, including 115, the call centre run by the emergency social services, as well as the French Red Cross.

Determined, constantly in a hurry, and paring her actions down the essentials, Victoria lives life at 100 km/h. At 28, her days are devoted to creating social impact and she doesn’t bother with detours or taking the long way round. Perched on two packing boxes during her lunch break, she answers our interview questions simply, precisely and directly, her voice hoarse from a persistent cough.

“I don’t pretend that on my own I’m changing the world, but by helping a few people, I am making my contribution and improving the system as a whole. That’s something.”

Tell us about yourself

In 2017, I joined Audencia’s Grande École Master in Management programme as part of the Management and Engineering double degree track in partnership with ECE Paris. I already had a social entrepreneurship project and some technical skills, but I lacked a business plan. I joined Audencia, which I saw as the school of audacity and social responsibility.

At Audencia, I was a perfect fit for the school’s trademark hybrid technical-business profiles. However, I also believe in the hybrid association of audacity and impact, and that was what I was looking for above all.

At the beginning, I devoted a huge amount of time bringing my business skills up to speed, especially in accounting (I’m so grateful for this because I use them every day). Then I headed to San Francisco to a summer school at Berkeley, which was an incredible experience in many ways. I took courses in leadership, innovation and yet more, advanced, accounting. I learnt so much in three months, especially since Berkeley is so ahead of the game in sustainable innovation and social entrepreneurship.

When I came back, I switched to the Master in Entrepreneurship with the Social Economy option. I was lucky enough to be able to follow this course and immediately apply my academic learning to my project, Solinum. Learning through experimentation and immersion was very powerful and exciting and a real added value of the programme. On the other hand, my timetable was a challenge because Solinum was starting to take off and I had many appointments: I often found myself travelling back and forth between Nantes and Paris.

Tell us about Solinum

Solinum is a social start-up that stems from two observations: on the one hand, contrary to popular belief, more than 70% of people living in precarious situations have access to a smartphone, and on the other hand, digital technology is not a dehumanising factor. On the contrary!

If used wisely, digital technology can be used to promote inclusion and care.

Since I have been working in the solidarity sector, I am struck by how slow digital transformation can be. Some multinationals have colossal resources at their disposal just increase a tiny degree of margin, but the associations serving human beings still work with paper and pencil.

When someone asks me whether it’s tech or social impact that characterises Solinum, my answer is clear: the two are inseparable. Technology must serve social impact.

Far from the image of a young engineer with geeky tendencies, then…

If geek means being a video game fan, then yes, I am one, in a way.

I’m especially passionate about automation. I love prototyping! In fact, I hate doing the same thing twice: if you need to do something again, there’s something you can create to save time and maximise the ratio of effort to impact.

In the field of solidarity, this is a very important concept because this is where technology puts the human element back at the heart of the matter. When we save time and and increase reliability on actions with limited added value, we can concentrate on the essential: the human element, the interaction, the encounter.

On the other hand, I also believe that innovation can be very sober. This might sound like a paradox for an engineer, but I don’t support innovation for innovation’s sake. The best tools are sometimes the simplest, especially if they are effective and meet the needs of users. That’s what’s essential in tech: meeting the needs of users, whether they are multimillionaires or homeless.

Why did you choose to focus on homelessness services?

I have been a volunteer ever since I was first a student, distributing meals and warm clothes and providing support to homeless people. With Soliguide, a platform for directing people experiencing homelessness to the services they need, I created the tool I needed as a volunteer.

The starting point of Soliguide was an existing need. In order to point people in the right direction, volunteers compile all the useful information in the field of food aid, socio-professional support, hygiene, health, training, learning French, etc. Then they have to check everything: is it possible to find the right person? Then we have to check everything: is a given structure open at a given time, have they changed their opening hours, is this aid still available, etc.?

Beyond collecting data, and putting it with other similar data, there was the question of making it reliable and available in a simple and practical way for all users, whether individuals or associations.

This is how Soliguide was born. It’s not an extraordinary invention, just a tool that’s simple and uncluttered but extremely powerful because it’s designed to be shared. To make access as easy as possible, we have multiplied the channels with a website, an app, paper lists, a Whatsapp number, etc. We even created the Solidarity API to enable other organisations to retrieve our data and use it to deliver their own support solutions. For example, the Entourage Association, which creates links and local activities for excluded or isolated people, works with our data: we don’t see this as competition at all, but as essential cooperation supporting people in insecure situations.

How does Soliguide work in practice?

Our work essentially consists of collecting, cross-referencing, making reliable and delivering data. Soliguide currently has nearly 50,000 services listed for people experiencing difficulties in 29 departments across France. I am very proud to say that we now cover over 50% of the French population. In 2022, Soliguide enabled more than 1.5 million searches: we can count our impact terms of in hundreds of thousands of lives.

Solinum welcomed its first employee in 2018 and today there are 32 of us raising funds, rolling out projects and circulating our actions to people and organisations working in the solidarity sector. Above all, we co-construct with them because we don’t copy our projects from one territory to another, we adapt them to local realities.

We are subsidised by local and state authorities, particularly because we facilitate the work and increase the impact of social actors. We discovered that we were saving society money and improving the efficiency of public policies: we avoid duplication and holes in the system and we rationalise public decisions. This became very clear during the pandemic.

What impact did the pandemic have on Solinum’s activity?

We were extremely busy in the departments where we were already established and word spread very quickly to the other areas that asked us to deploy urgently. It wasn’t always possible but we did our best.

Imagine how tough lockdown was for people on the street: how did they know what was open and what was closed, how did they know where to find food, etc.? The information on Soliguide enabled us to set up alerts when, for example, all the services in an area were closed.

At the outset of the pandemic, we only covered seven departments and we noted an overuse rate of +200%. In 2021, thanks to an extremely tight deployment methodology, we opened fifteen new departments, which prepared us for the Ukrainian crisis, to which we reacted immediately by translating Soliguide into Ukrainian and identifying the specific structures most needed by refugees from Ukraine.

These successive crises highlight the importance of real-time information for both individuals and public authorities. What we are looking at today is the use of data analysis for social policies in each territory.

You mentioned Solinum’s financials; it’s hard to imagine the solidarity sector being a good fit for a young management school graduate

Let’s face it, my parents would probably have preferred to see me follow a more lucrative career path but it’s one that is in tune with what I want from life. If I earned more by doing something else, would I be as happy? I don’t think so.

That doesn’t mean that you can’t earn a salary by working in this field, the lines are moving on that, but obviously you earn less than in a big company that is destroying the planet.

I earn enough to satisfy my needs. I have enough to satisfy my material needs while still being able to satisfy my immaterial needs, give meaning to what I do and make me want to get up in the morning. The only absolute resource we do have is time, but are we using it wisely? I don’t want a life where I start the week thinking: “Can’t wait for Friday!” or “I can’t wait to be somewhere other than my job!”

My ratio is to earn enough to afford what I need without squandering my time at the expense of the planet, society and myself. The difference in salary is therefore the price of my personal wellbeing.

What is it like to be a woman leader in the solidarity sector?

As a young woman, you’re kind of looking for trouble!

I have been asked more than once if I was the trainee. Beyond the anecdote, which doesn’t hurt me too much, it’s clear that my credibility is at stake. In all walks of life, people look to men first, even in this sector where there are only women in the field. The French only have the feminine term for “social worker”, by the way.

We are in a female-dominated sector, but, more often than not, directed by men in the round table events and on the boards of directors.

I try to make my own path and get things done; actions give credibility. I don’t take offence at what people say or think, I always try to move forward and build on what I achieve.

It’s vital that we look at diversity from another angle, including from the homelessness angle, which is much more contrasted than people imagine. We are not just talking about homeless men, but also about young LGBTQ+ people rejected by their entourage, women escaping violent or abusive relationships, entire families impoverished by migration or social breakdowns. This image of homelessness being a male environment has always been false but today it is increasingly untrue and the pandemic has not helped. We are seeing more and more students using soup kitchens; they used to hold down summer jobs but these disappeared after the pandemic.

The subject is not me or the way people look at women leaders, the subject is how we can all work better together, how we can multiply the viewpoints to better understand and deal with the problems.

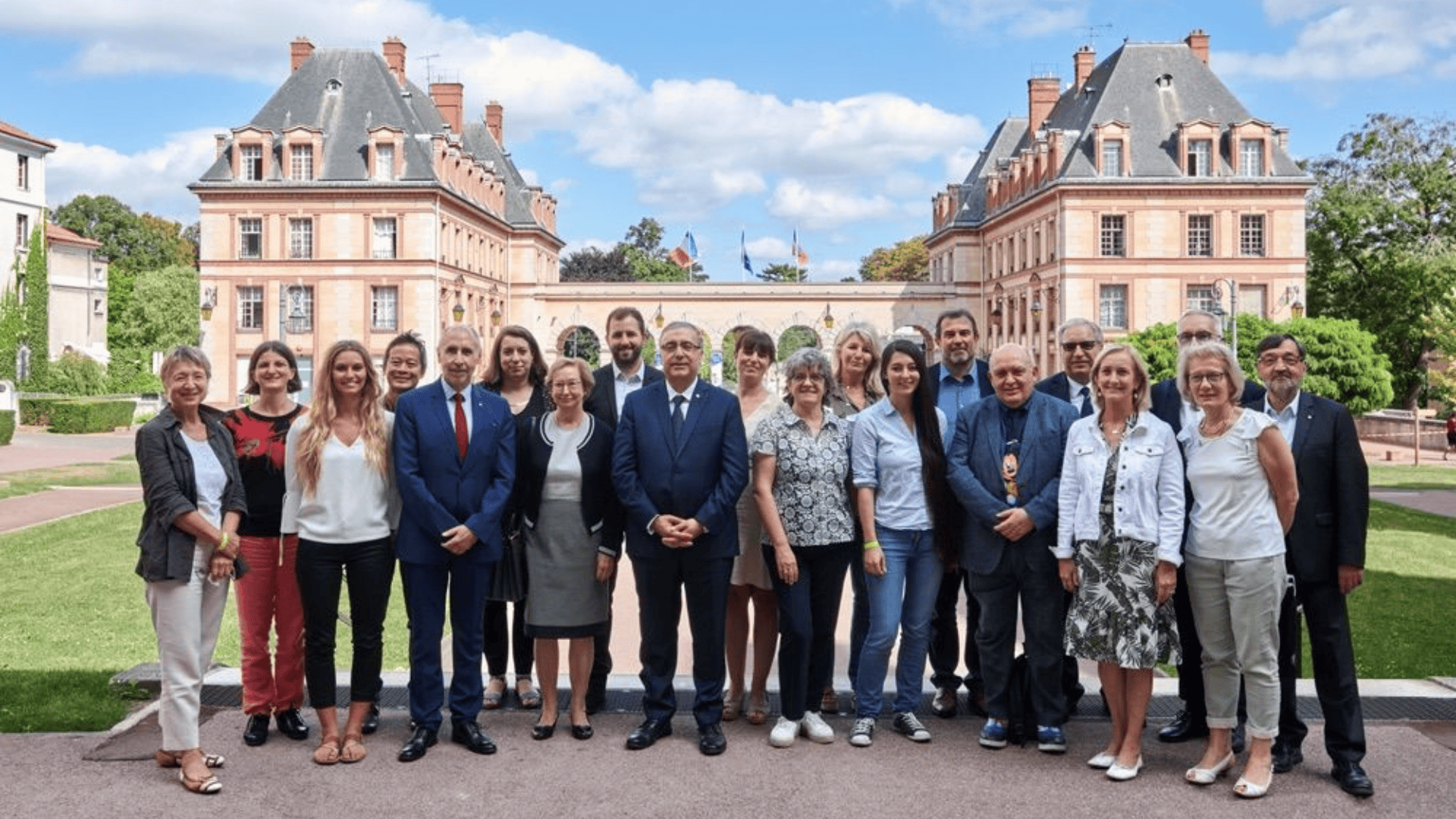

You are also on the board of the French Red Cross, what does that entail?

I joined through 21, the Red Cross social innovation accelerator, when Solinum was supported for six months as part of a call for projects, and I fell in love with the organisation. That’s how, two years later, I ended up on the board.

The Red Cross is a very big machine, which may seem slow and heavy to an entrepreneur, but when it moves, it moves powerfully. In an emergency, we know where to be.

I’ve been on the board for a little over a year now. It’s a voluntary position that takes up two days every three months, in addition to the working committees. We study the Red Cross’s legal and strategic orientation to stay on target with the 2030 plan.

The volunteers have a variety of profiles, often with lots of experience, and I am happy to represent the younger generation. The different experiences and points of view enrich the debate, on ecological issues for example.

If you had to give one piece of advice to today’s students, would it be about engagement?

No, engagement is my thing, but not necessarily everyone else’s. I would tell students to search for what makes their heart beat faster and to go for it. Above all, I would tell them that all choices are justifiable even when they don’t seem to be part of a preordained or obvious path.

What can we wish you for the future?

For Solinum, to continue to grow. I don’t want us to become a big organisation, but I do want us to increase our impact. The curve must be exponential as we need to reach more and more people in France and then elsewhere, without increasing our costs tenfold.

For myself, just to finalise my move. My 30th birthday is not so far off and I’m finally leaving my tiny basement flat for somewhere bigger. Just goes to show, anything can happen.

Victoria is founder and CEO of Solinum, a social start-up that she created in 2016 and which publishes the platforms Soliguide and Merci pour l’Invit’, a network of citizen accommodation for reintegration. A board member of the French Red Cross, Victoria is one of Vanity Fair’s 30 under 30 and Carenews’ Top 50 impact entrepreneurs. Her actions and engagement regularly receive recognition; AACSB has recently named her an Influential Leader in their class of 2023.